We Went To Bengaluru, India, and Presented Our Work!

Reflections from the Mapping Data Work Workshop in Bengaluru, India

In March 2025, we had the opportunity to represent the AI + Planetary Justice (PAIJ) Alliance at the Mapping Data Work Workshop in Bengaluru, co-organized by the University of Amsterdam, Aapti Institute, and Tattle. The event brought together scholars, activists, and practitioners to collectively examine one of the most overlooked components of artificial intelligence: the human labor that makes AI possible.

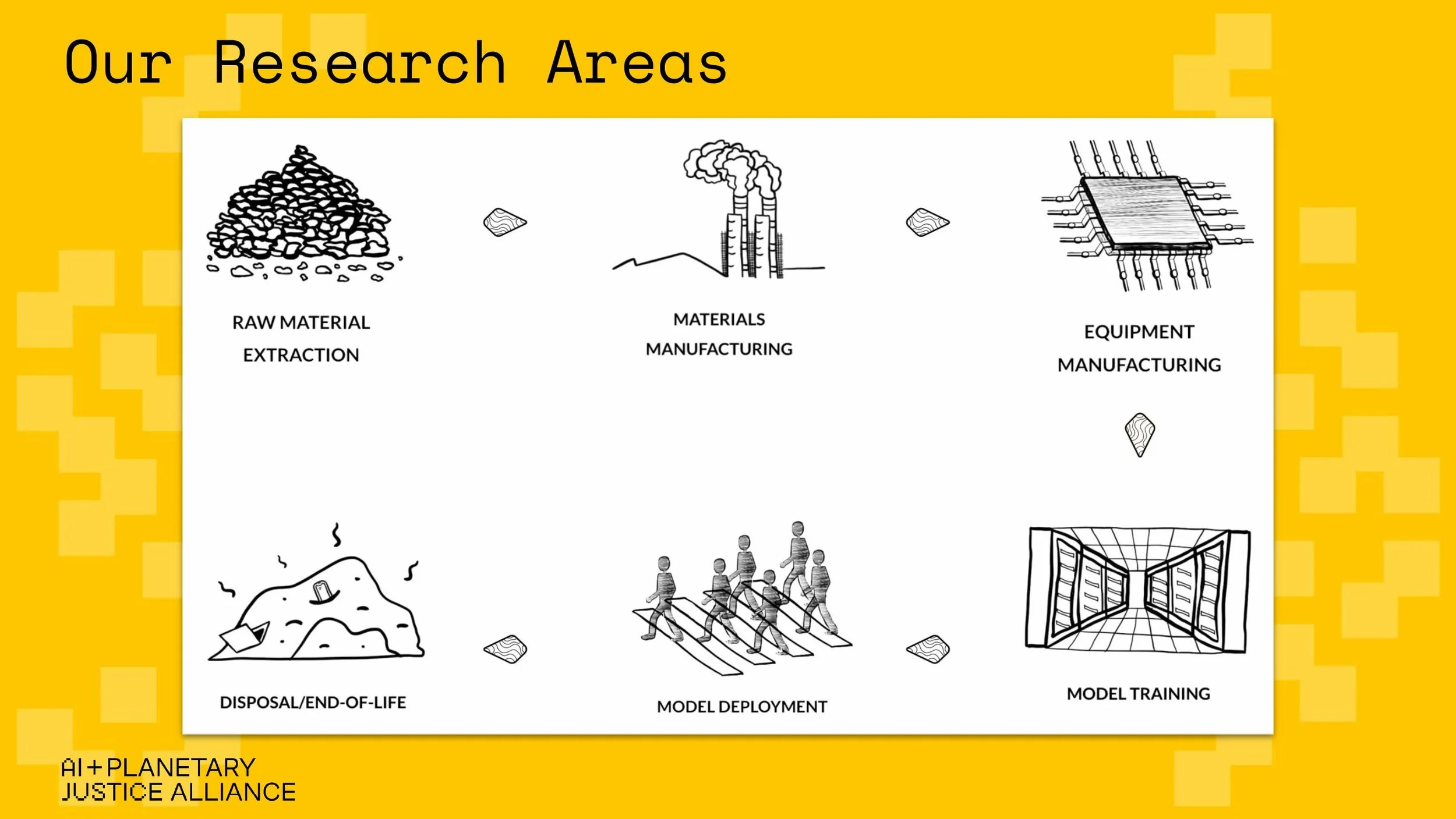

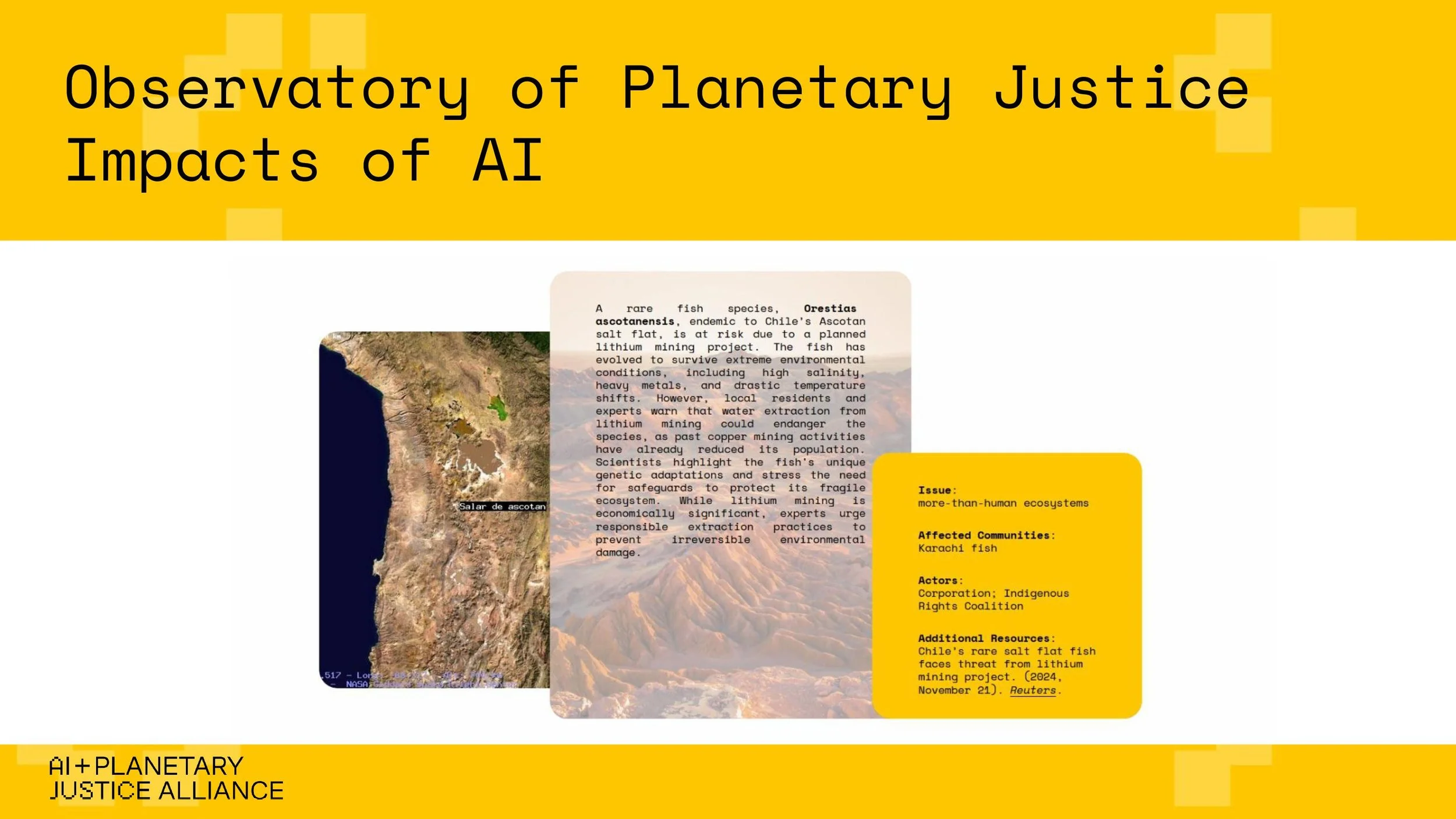

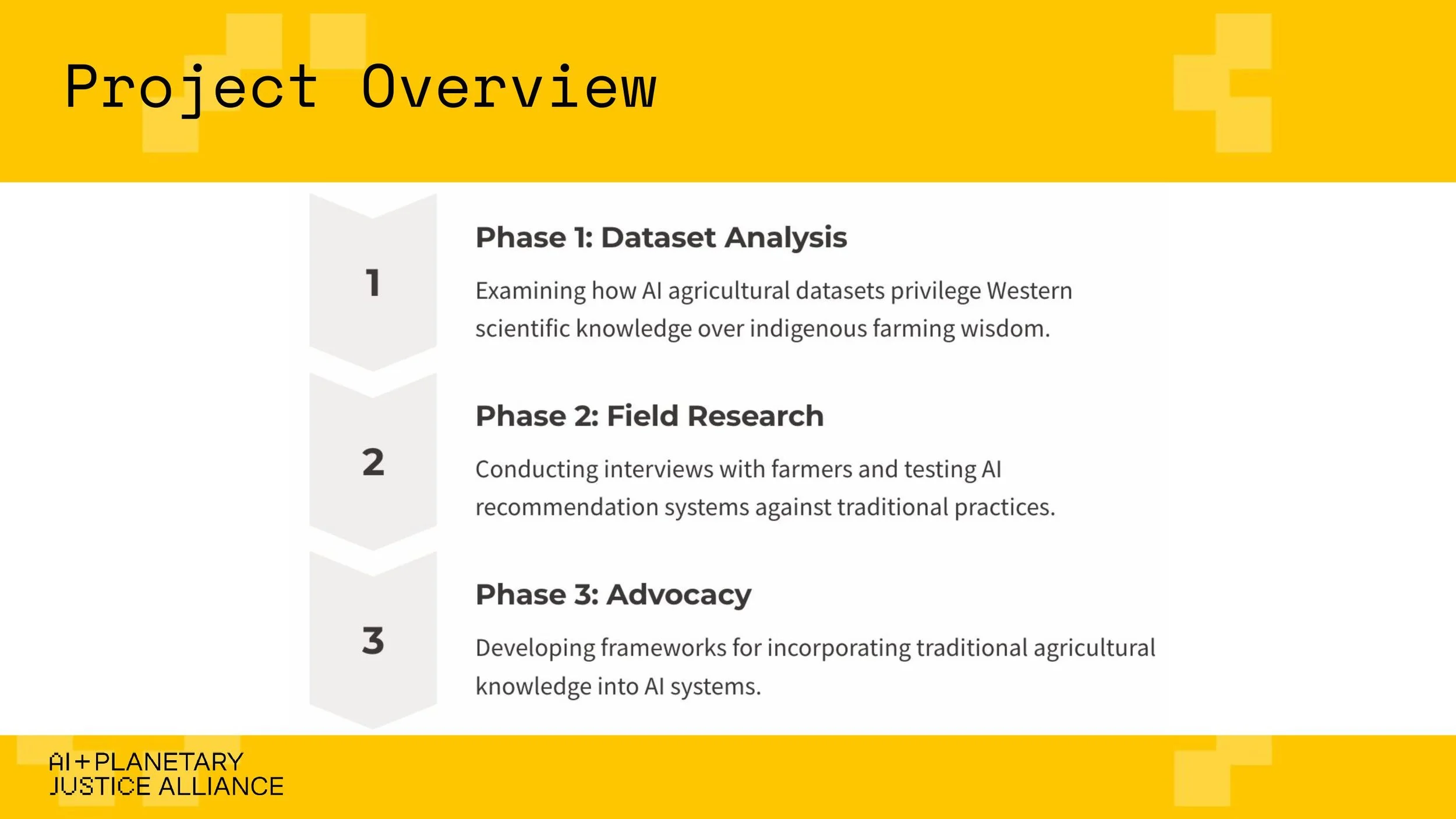

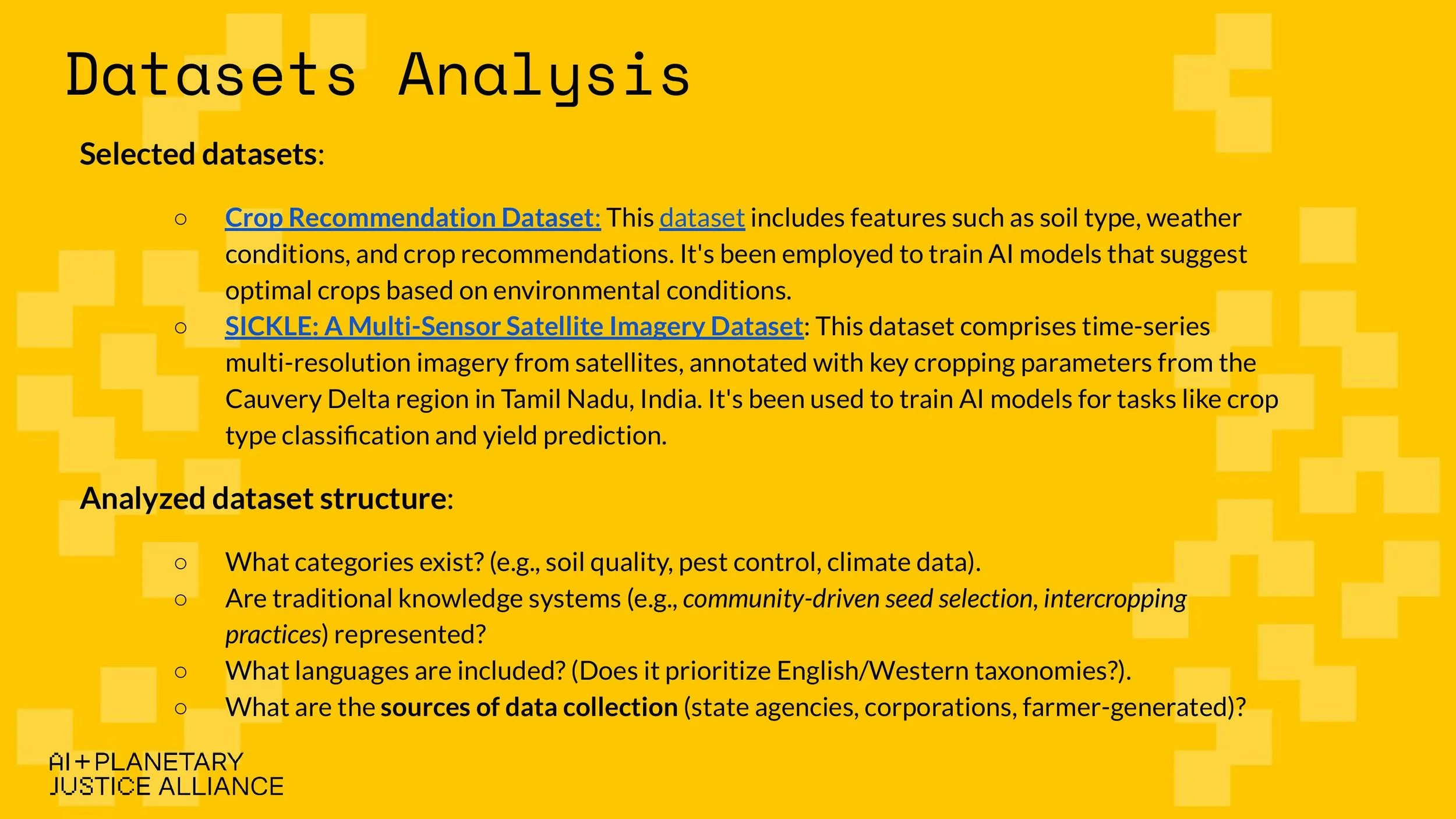

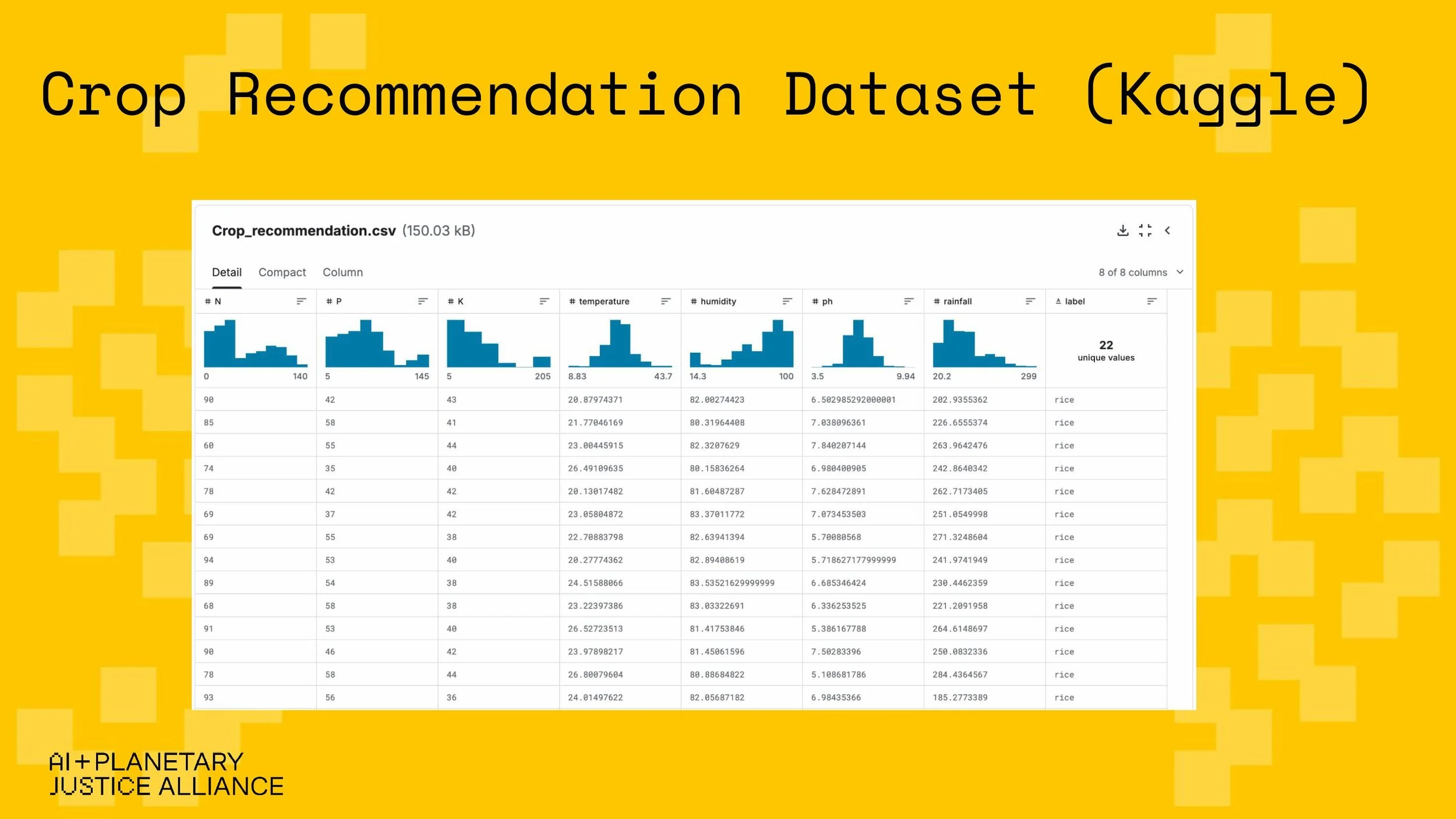

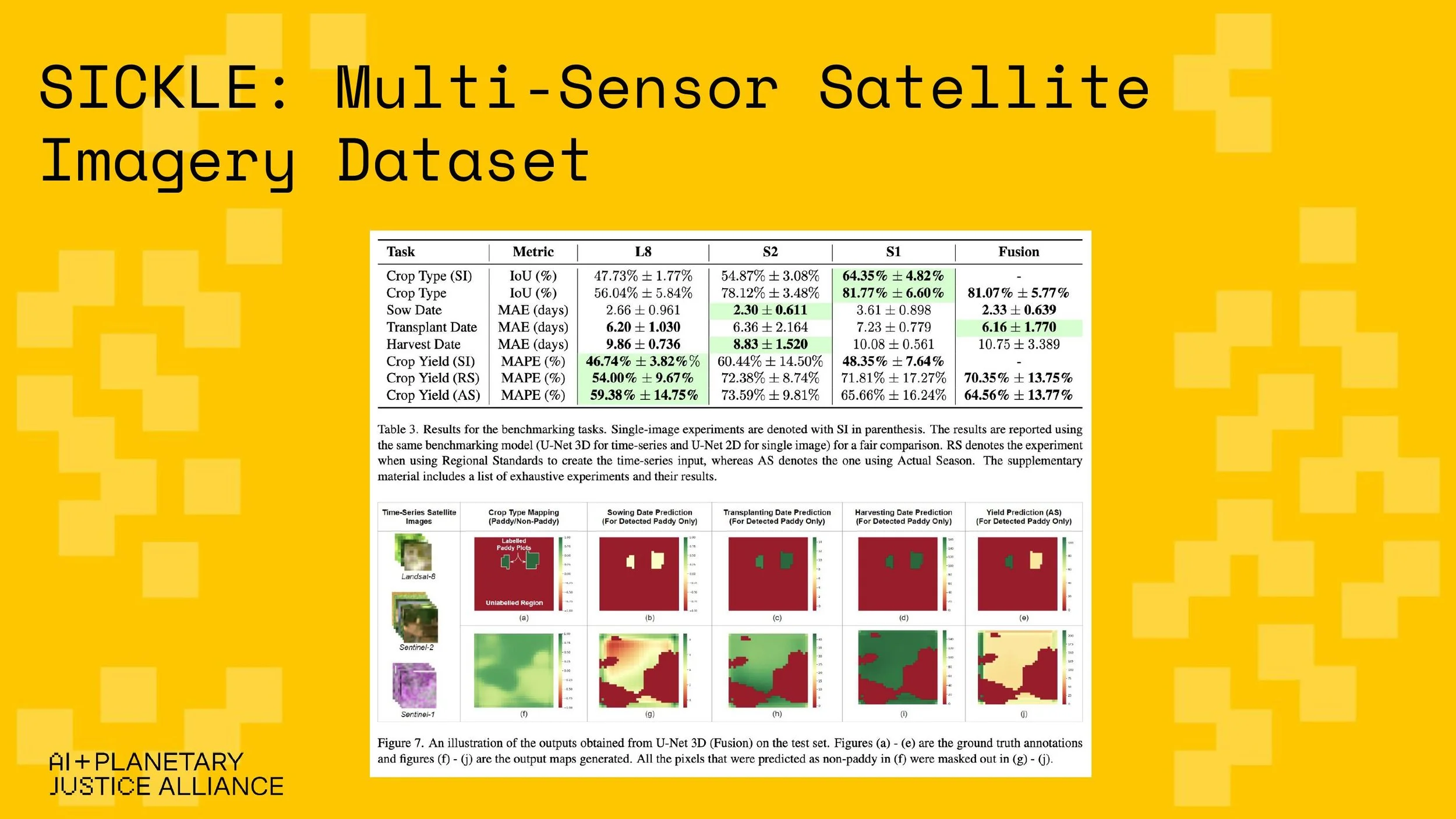

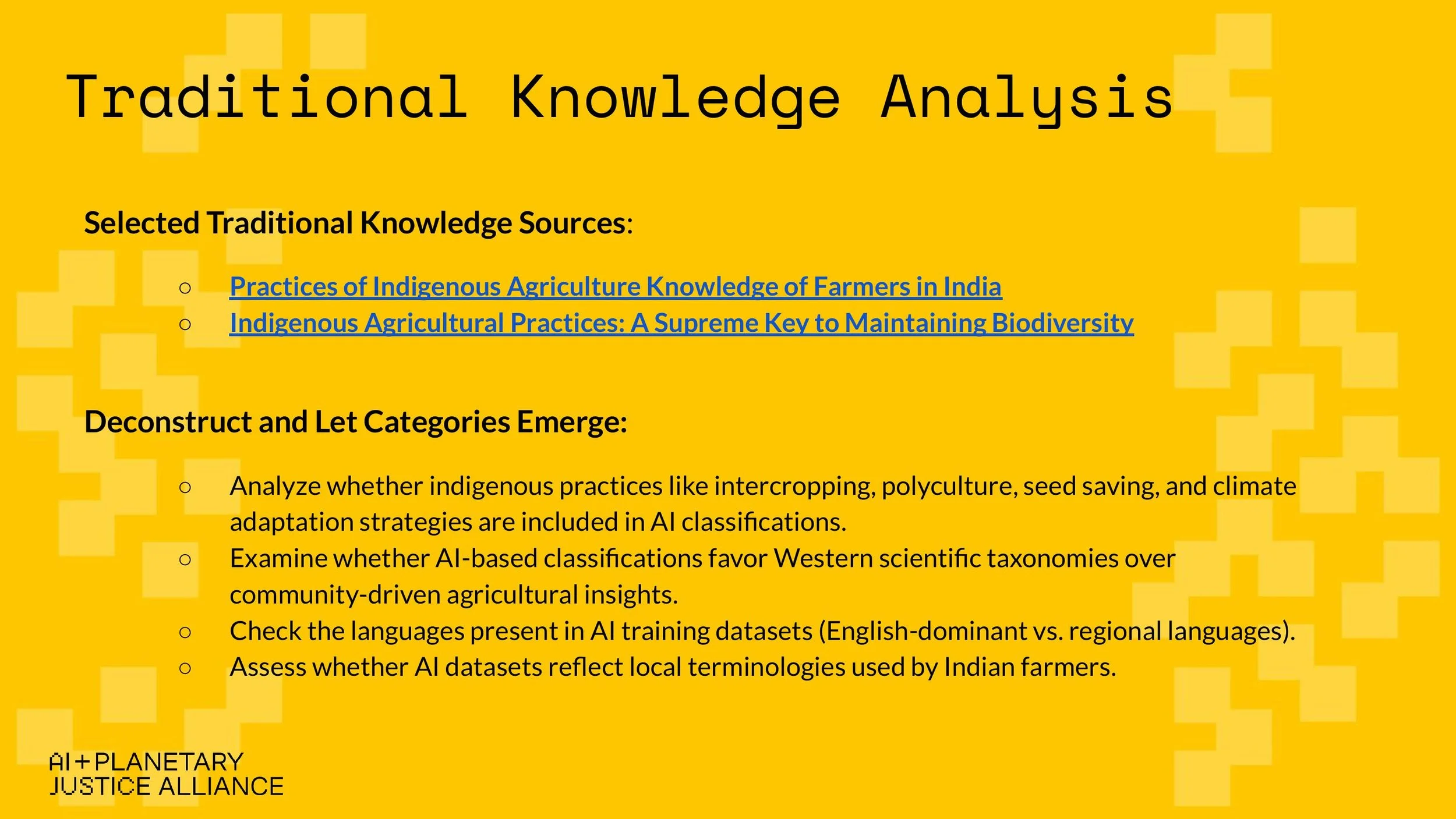

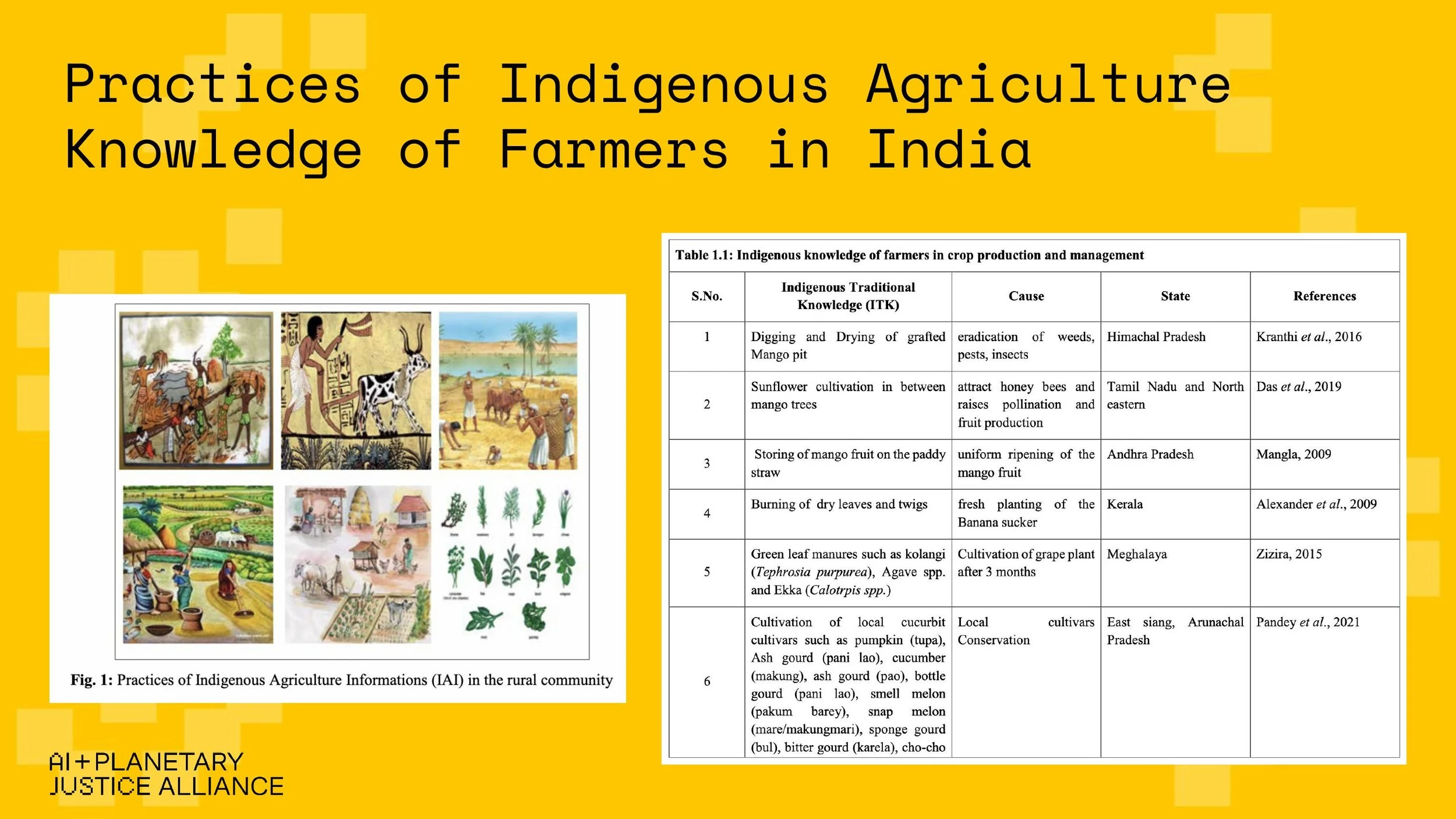

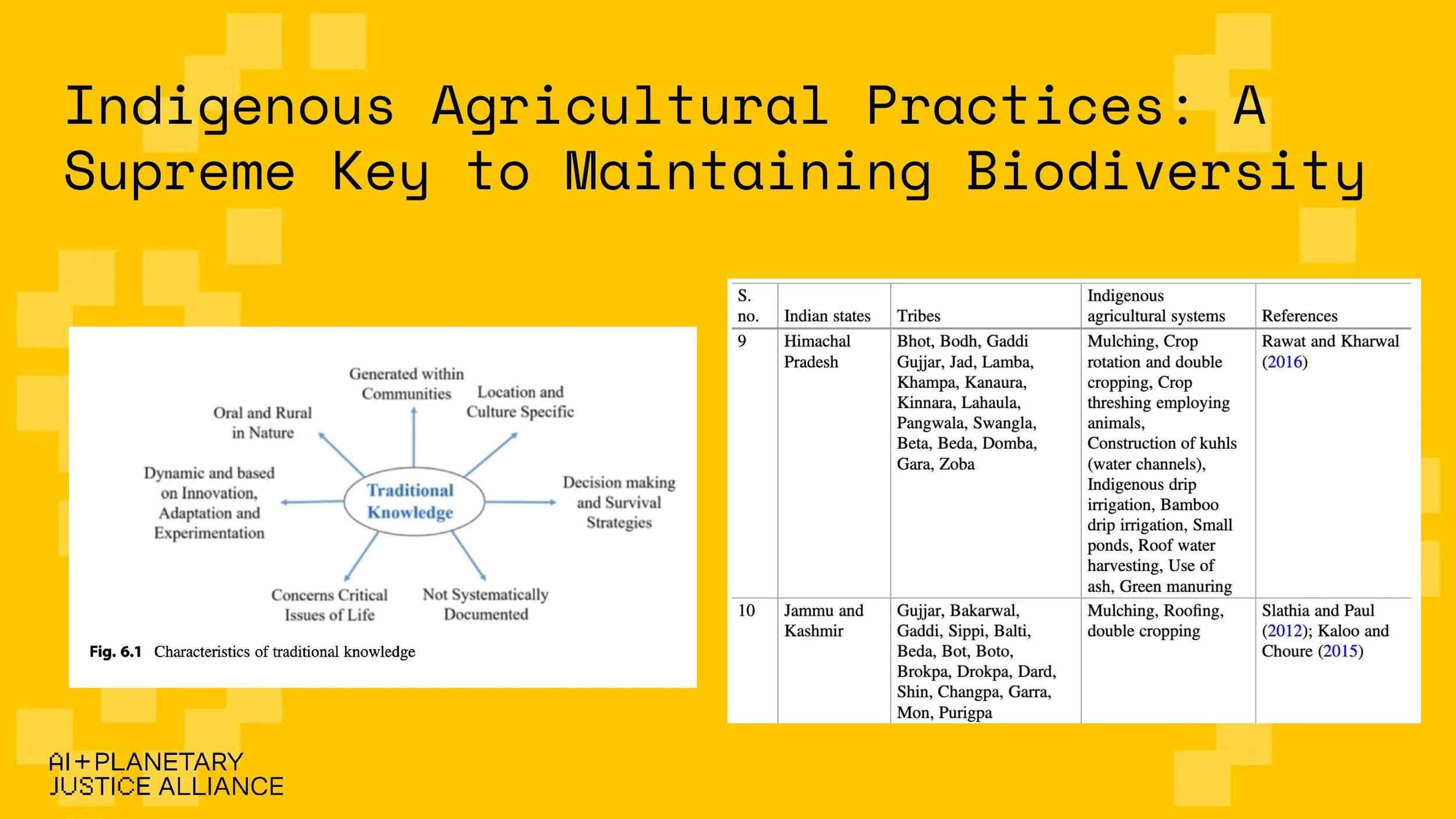

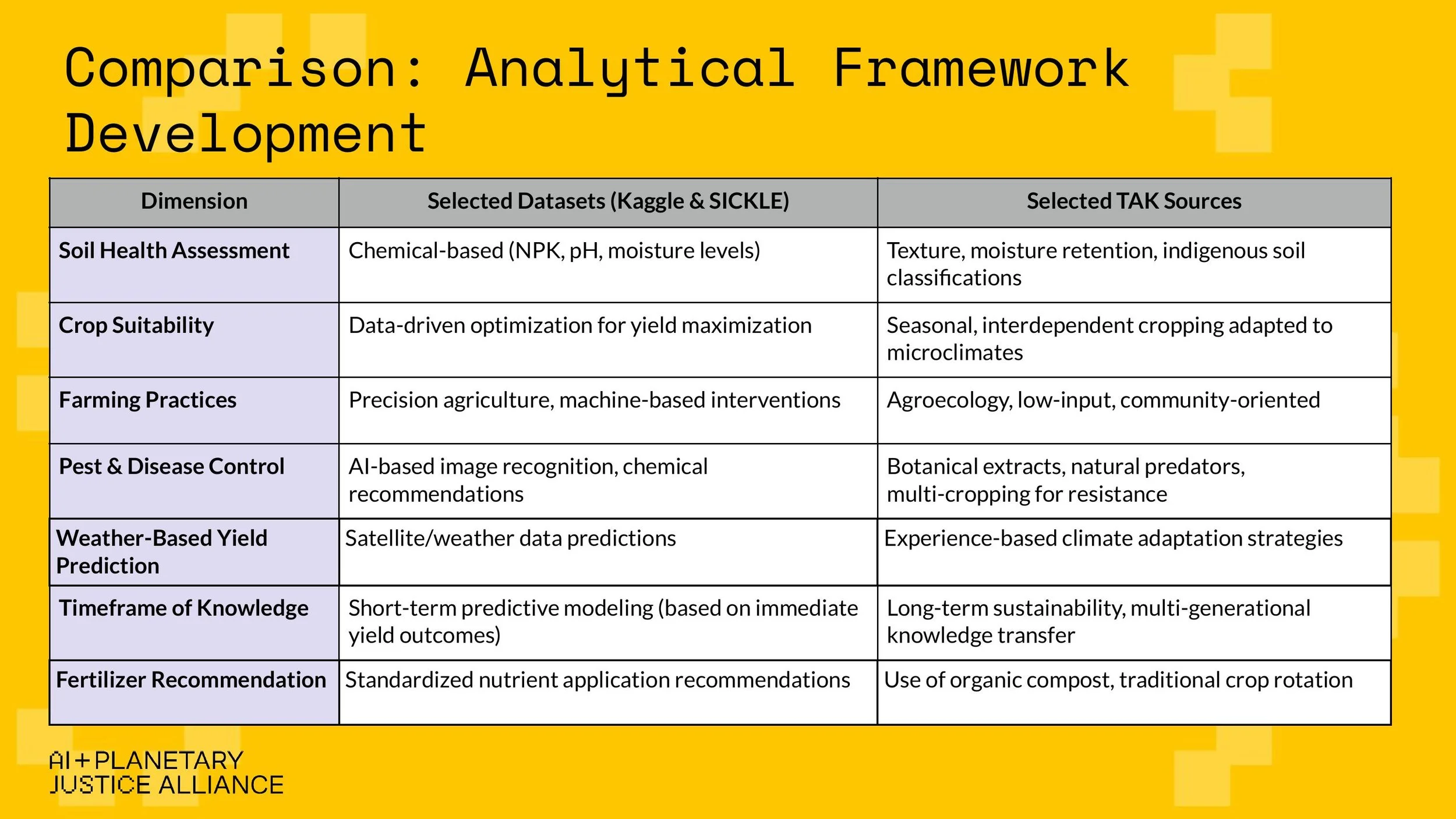

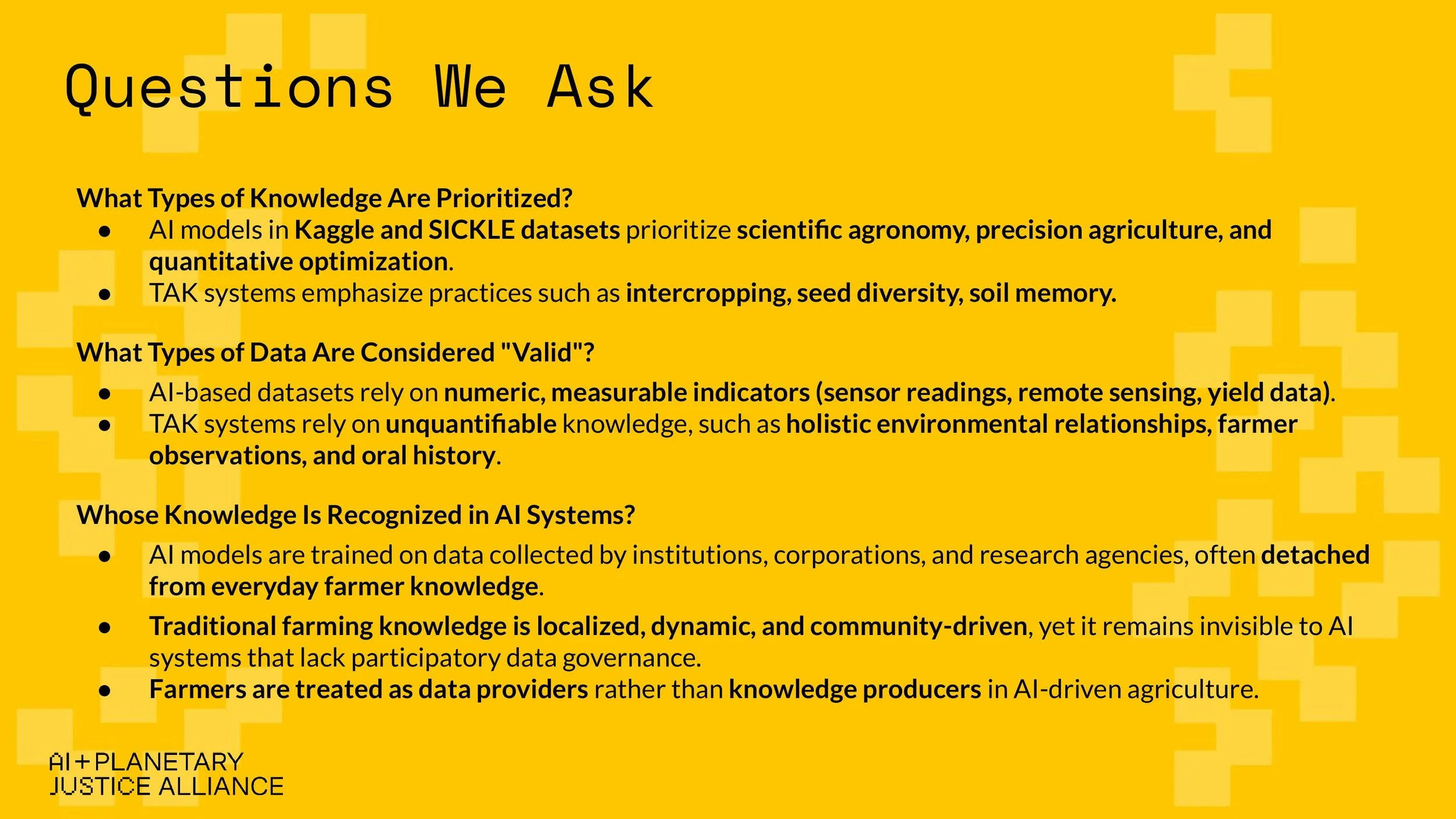

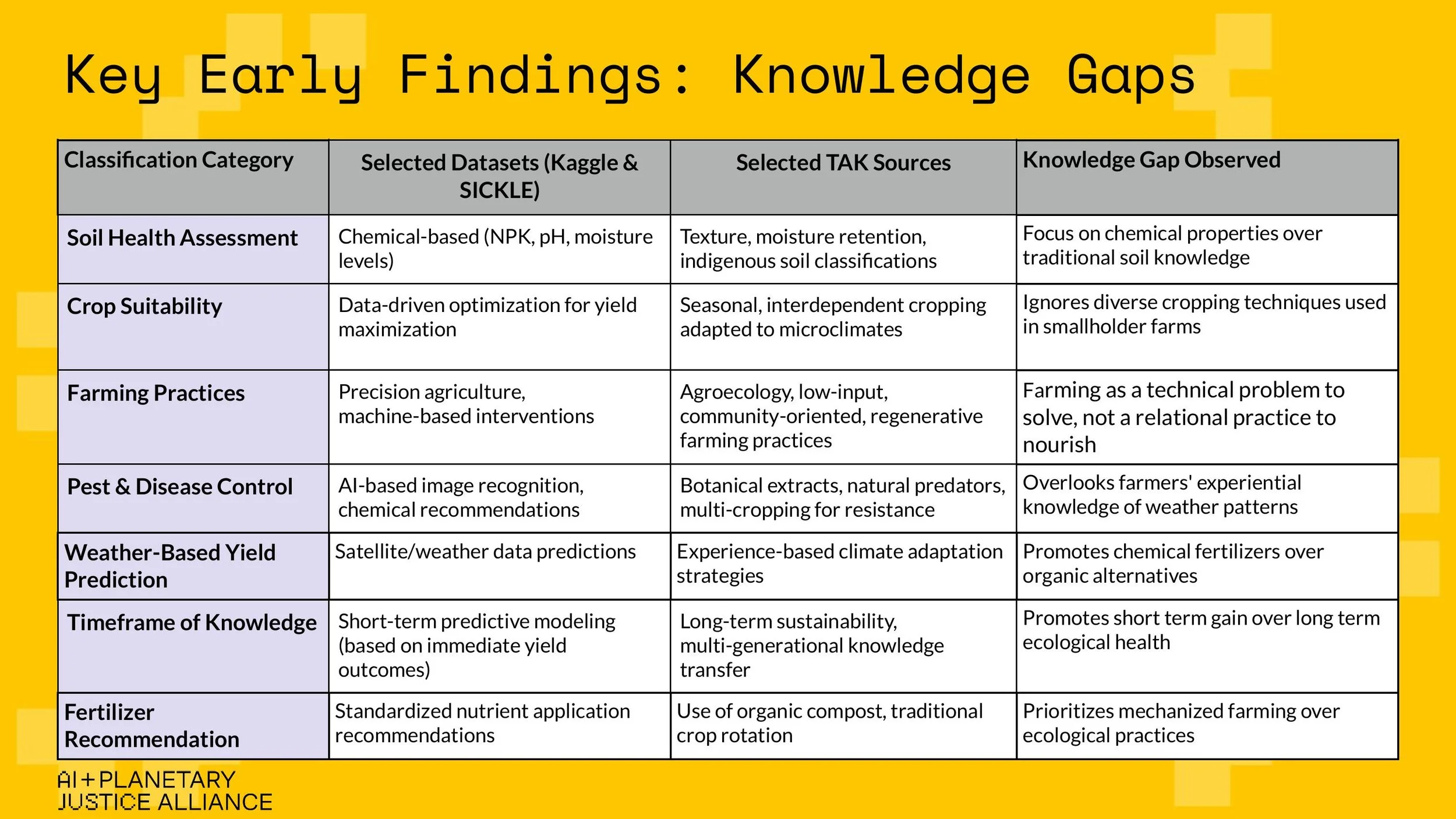

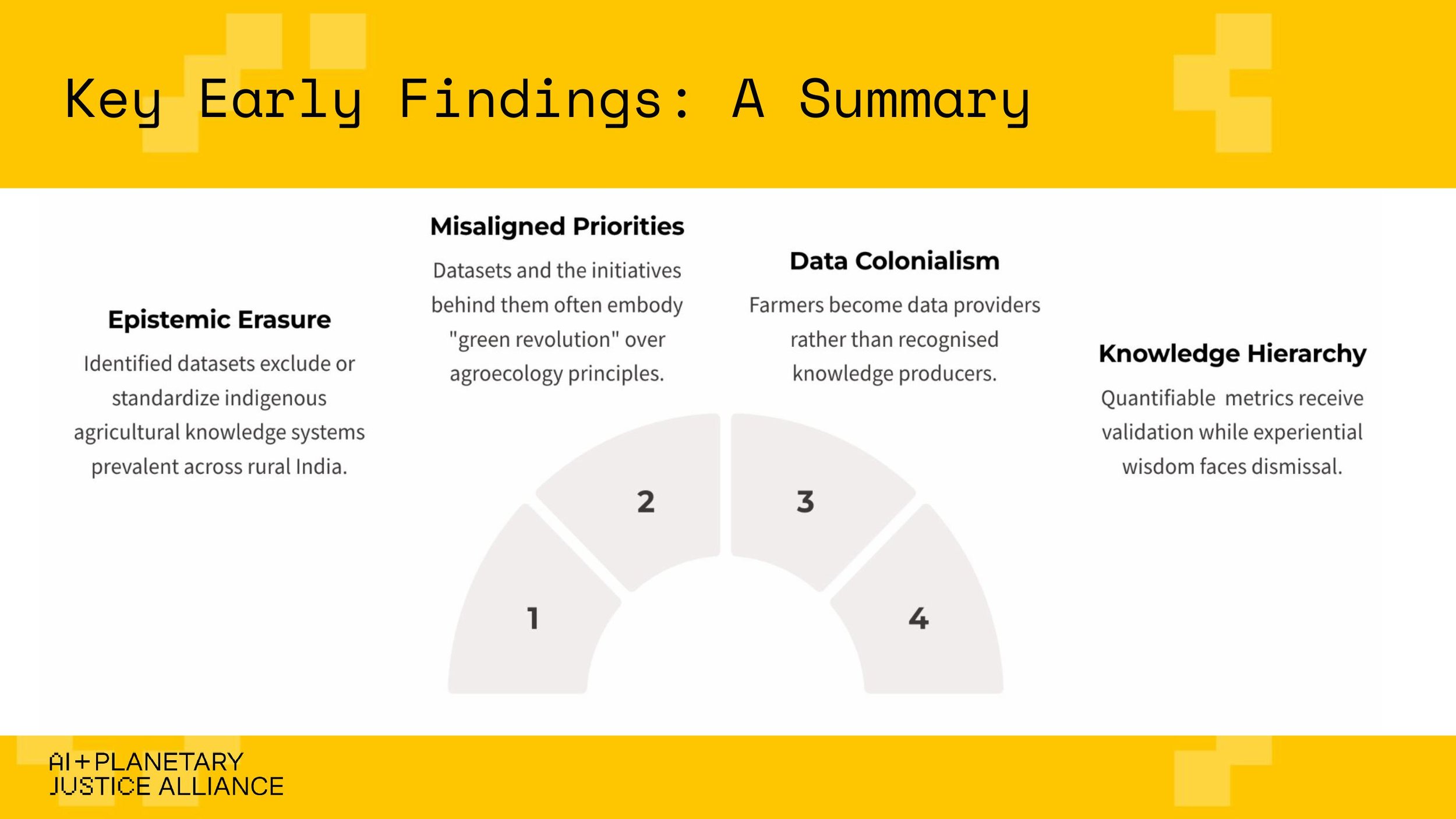

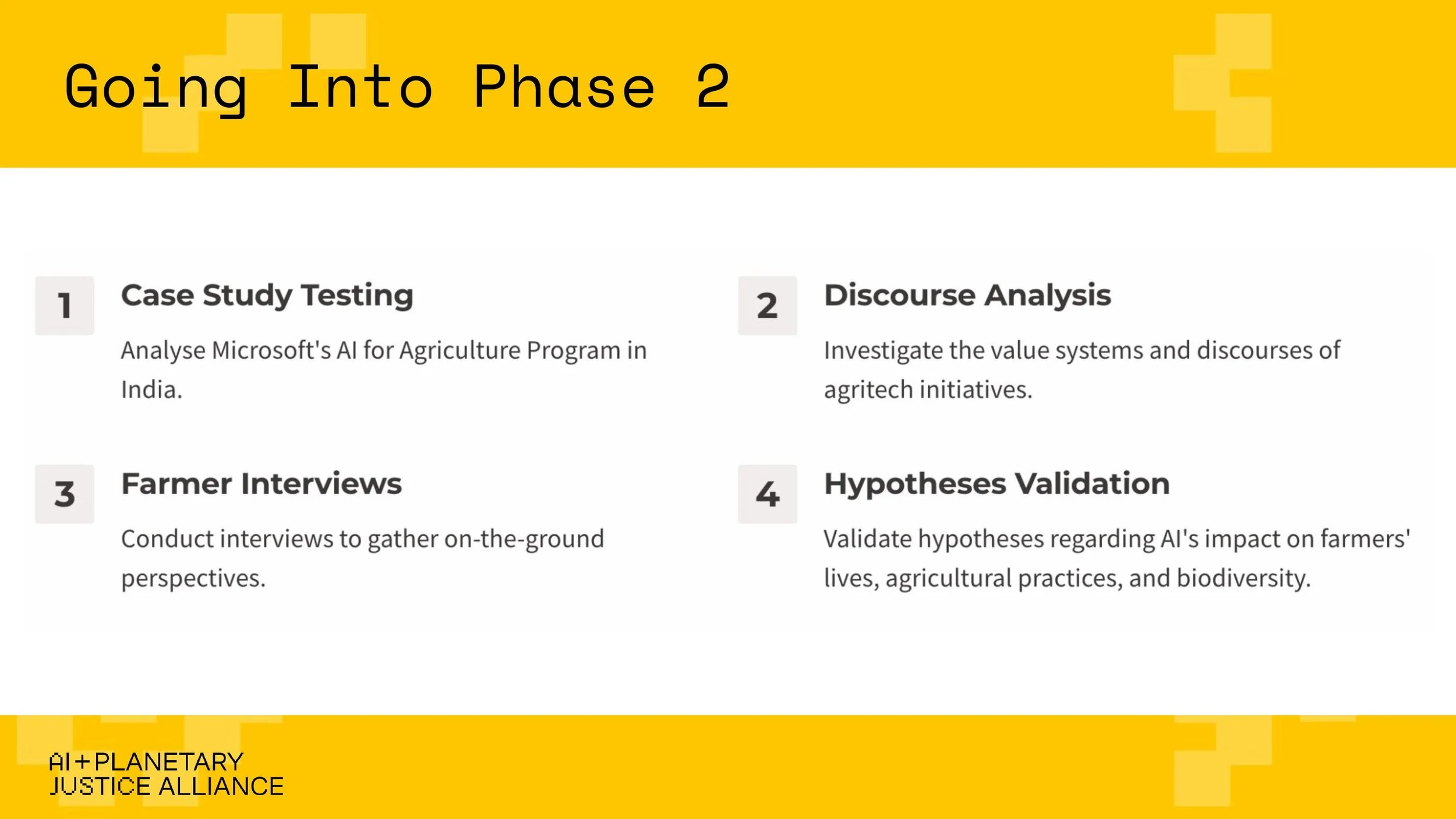

At AIPJ, we work to map the socio-environmental and epistemic impacts of AI across its supply chain–from raw material extraction to disposal. Data work sits squarely at the center of our "Model Training" research area, and the workshop reaffirmed just how invisible yet essential this stage of the AI lifecycle truly is. We presented the AI + Planetary Justice Alliance, and the early phase of our new research project, Toward Epistemic Justice in AI Datasets: Data Work and Agriculture in India, which is part of our Model Training research area. The project investigates how agricultural AI models–often trained on datasets built on Global North epistemologies–risk excluding the contextual, generational knowledge of smallholder and Indigenous farmers. We were there to share early insights, gather feedback, and refine our methodology alongside others doing deeply aligned work.

The slide show we used to present.

Over two days, the workshop exposed the layered realities behind AI systems that are often imagined as disembodied or immaterial. We heard from data annotators, content moderators, and organizers who shared firsthand accounts of the precarity, invisibility, and psychological toll embedded in these jobs. Many of these workers–particularly men and women in India and across Africa–are bound by nondisclosure agreements and operate within opaque subcontracting structures that obscure who they are working for, how their work is valued, and how their data is used.

We began by mapping the historical roots of data work, tracing its continuity from earlier outsourcing regimes to today’s AI value chains. Workers and organizers spoke powerfully about the reality of labeling, annotating, and moderating data–much of which happens under precarious, low-wage conditions in India and across Africa. Despite their central role in AI development, data workers are kept at arm’s length from the AI systems they help train and are often bound by NDAs that limit their ability to speak out.

Other sessions highlighted the structural opacity of AI supply chains. Discussions covered platform governance, outsourcing layers, the complexity of consent, and the absence of adequate regulatory safeguards. An entire afternoon was dedicated to exploring alternative models of data work, including worker-led platforms, ethical datasets, and the challenges of balancing transparency, sustainability, and dignity.

One key takeaway was the myth of automation. Rather than replacing work, AI redistributes it–often to the margins. From moderating traumatic content to annotating satellite imagery for agriculture, the so-called intelligence of AI still heavily relies on human labor. Yet, these workers are rarely recognized as knowledge producers or compensated accordingly.

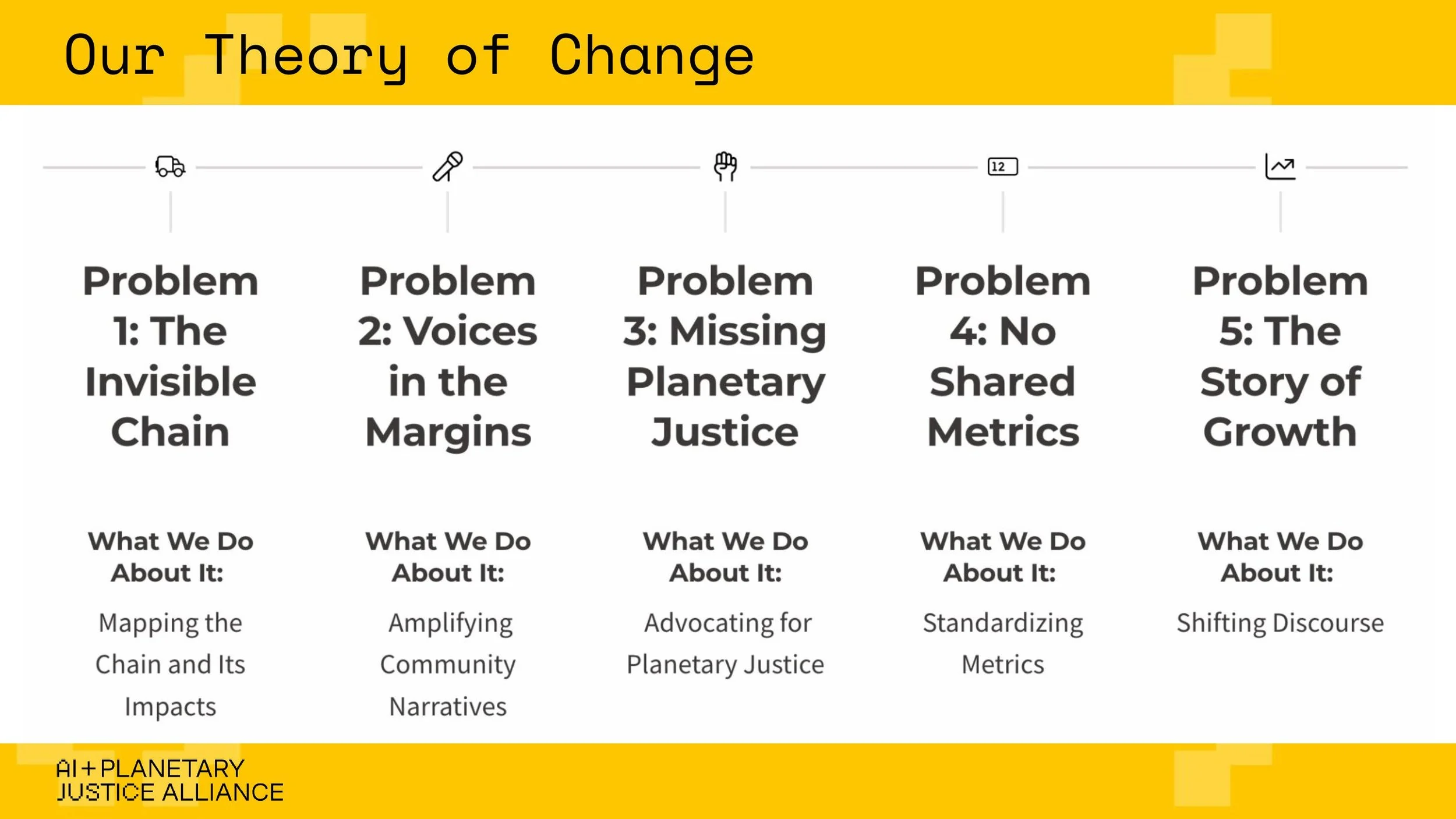

AIPJ is committed to making these stories visible: our theory of change begins with mapping the AI supply chain and its planetary justice impacts–something we see not only in mining sites and data centers, but in data work too. Participating in this workshop expanded our understanding of the labor struggles within AI systems and reaffirmed our commitment to building research and advocacy rooted in justice, transparency, and plural knowledge on how automated systems come to be.

At the end of the workshop, we were able to pose a series of open questions to all participants: What is the value of doing all this to begin with? Why are we building these AI systems at all? What justifies the vast and growing ecosystem of precarious labor that feeds it?

Data work exists because AI needs data. But do we need AI for everything we’re using it for? If the very purpose of the AI system is unclear or questionable–especially in contexts like agriculture, healthcare, or climate–then the data work sustaining it becomes even harder to justify. No dataset is ethically sourced if the system it supports serves no justifiable or collective end.

The idea of “ethical datasets” is also worth unpacking. Often, ethical data initiatives aim to ensure representation: of languages, communities, demographics. But what does it mean to be “represented” in a dataset? For whom? And to what end? When representation becomes a pretext for surveillance or commodification–when being seen means being captured, extracted from, and sold back to–it ceases to be empowering (read this blog for our view on the importance of refusal and agency).

This leads to a deeper question about the logic of datafication itself. Must we close the “digital divide” by rushing to include everyone and everything in the data economy? Inclusion into exploitative systems is not liberation, is it? Whether we should datafy a person, a community, or an ecosystem depends not only on how it’s done, but why. What is the value of any specific datafication process? Who benefits? Who loses? And can the benefits ever justify the costs?

These are the questions we’ll continue to carry forward in our work at the AI + Planetary Justice Alliance. Not only how to improve the conditions of data work–but whether some data work should be done at all, and–if so–to what end.