AIPJ at the Digital Citizen Summit in Hyderabad, India

Last week, we participated in the Digital Citizen Summit (DCS) in Hyderabad, a two-day gathering convened by the Digital Empowerment Foundation (DEF) and partners to create dialogue around technology, rights, and sustainability.

The Summit brought together a vibrant mix of practitioners, civil society organisations, technologists, researchers, artists, and policymakers. Rather than treating AI* as an abstract or purely technical phenomenon, the DCS created space for critical, grounded conversations on the material, social, and political foundations of digital technologies, especially in regions increasingly targeted for infrastructure expansion.

For AIPJ, this was an important moment to connect global research on AI’s supply chains with local struggles and questions emerging around Hyderabad’s growing role as a data centre and tech infrastructure hub.

*As always, when we at AIPJ talk about AI, we’re talking about large-scale, general-purpose, centralized models.

Day 1: Making the Hidden Infrastructure of AI Visible

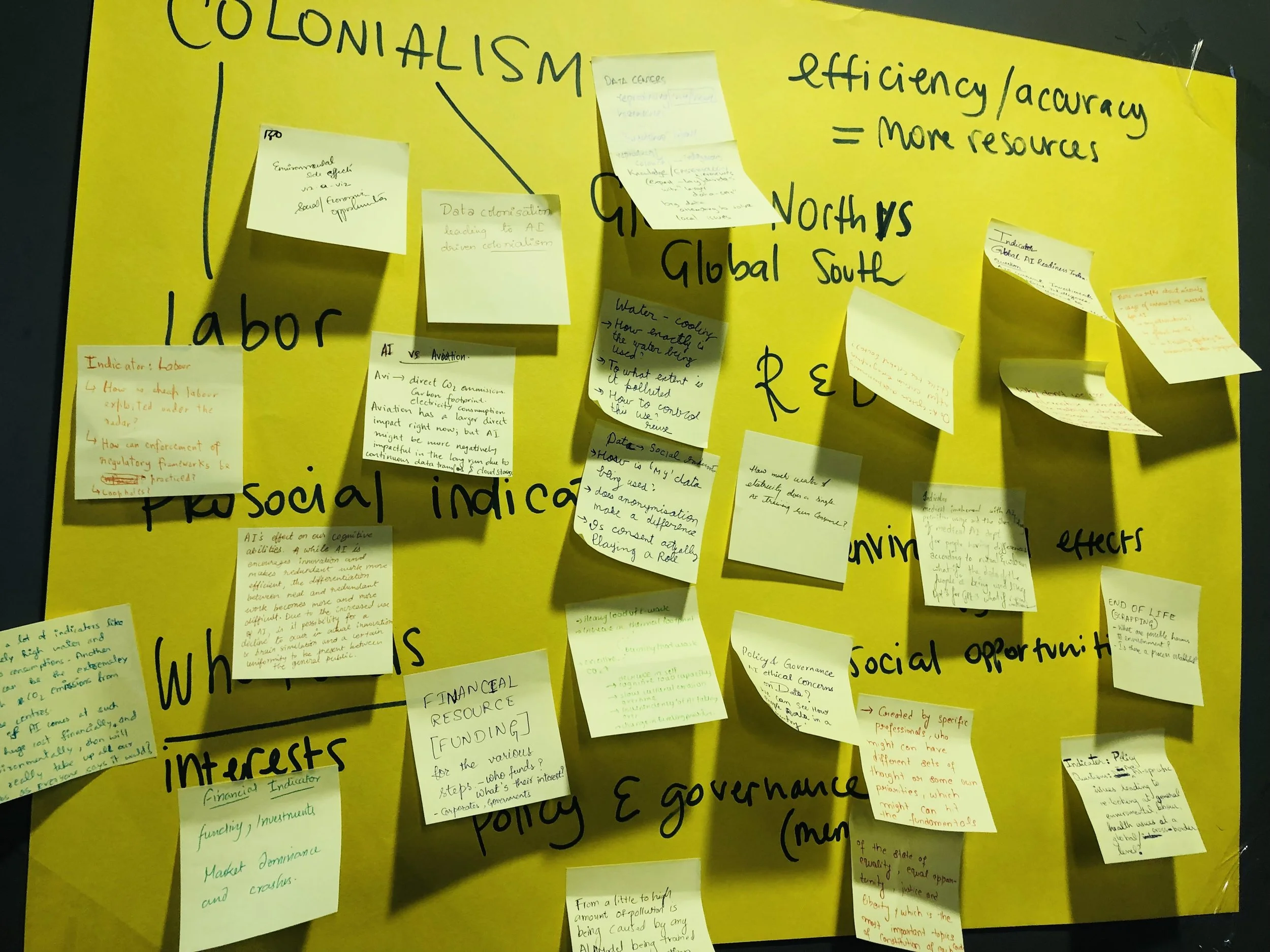

The first day of the Summit centred on a participatory workshop facilitated by AIPJ, focused on the model training phase of the AI lifecycle. Rather than approaching AI as an abstract or purely technical object, we framed it as something deeply entangled with land, water, energy, labour, and materials – and therefore with very real social and ecological consequences.

We began by unpacking what we actually mean when we say “AI”. Many participants shared how, in their daily work, the term is used as a catch-all for very different systems – from recommendation engines and chatbots to surveillance tools and predictive analytics. We slowed this down by distinguishing between different scales and types of AI (large-scale vs small-scale, centralised vs decentralised, general-purpose vs task-specific), and highlighting that what currently dominates global investment is a very specific model: large-scale, compute-intensive AI driven by corporate and geopolitical competition.

From there, we moved to a core argument: AI today operates as an industry, and like any other industry, it is built on a supply chain (that, in turn, is made of several interconnected supply chains). Together with participants, we traced this chain from mineral extraction and material processing, through chip and hardware manufacturing, to model training in data centres, deployment, and finally e-waste disposal. Rather than treating these as isolated stages, we examined how decisions in one part of the chain ripple across others, producing cumulative social and environmental pressures.

The workshop then zoomed in on model training, a stage that is often discussed in highly technical terms, but rarely in relation to its physical, territorial, and labour implications. We unpacked what training actually involves: massive data collection and cleaning, repetitive training runs on GPU clusters housed in energy-intensive data centres, the hidden human labour behind annotation and moderation, and the cycles of evaluation and fine-tuning that rely on both compute and people.

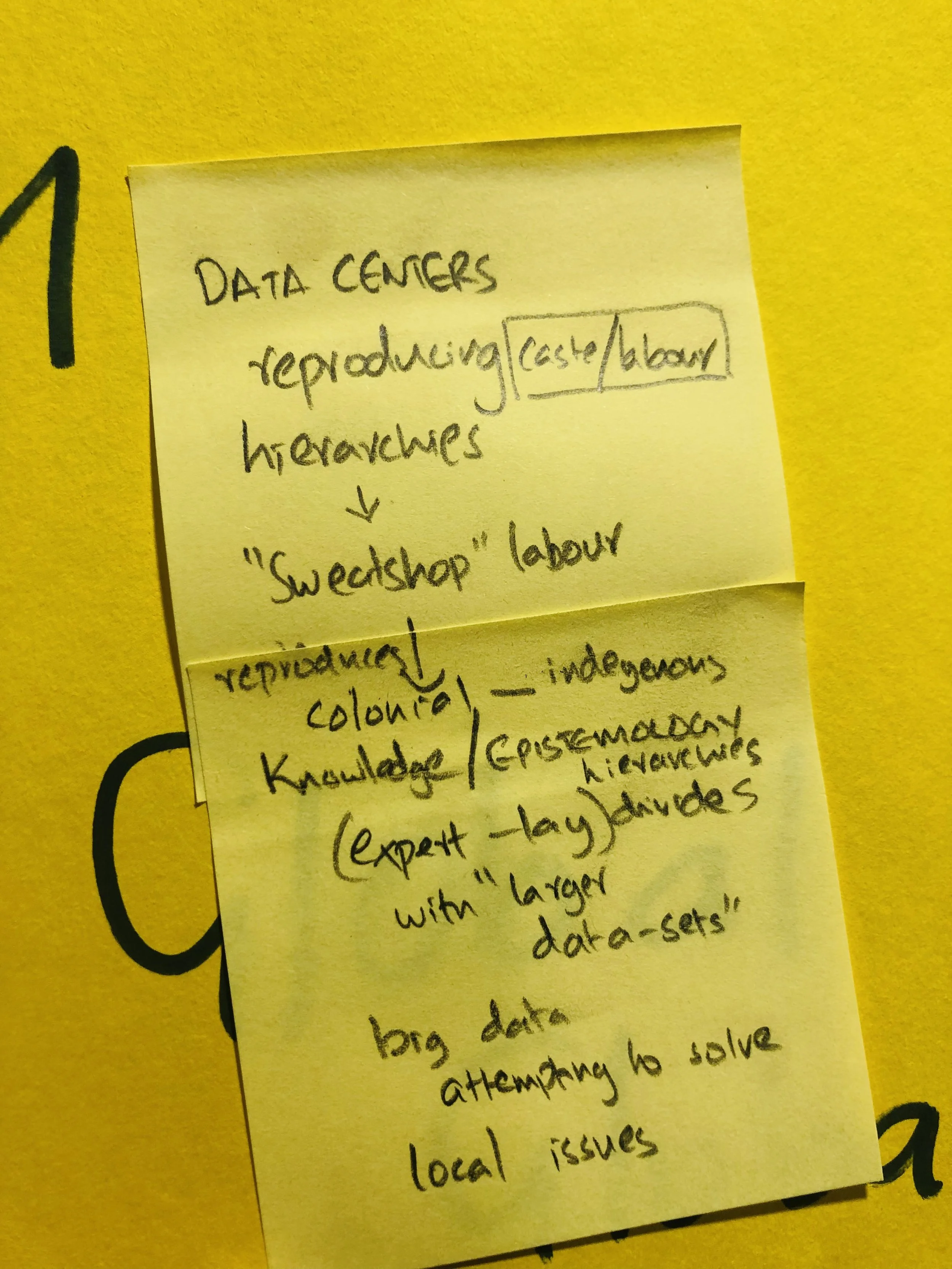

As participants collectively mapped these processes, several critical reflections emerged from the room.

One participant noted the tension between local economic aspirations and environmental impacts. In many cases, communities are promised development, jobs, and infrastructure through the arrival of data centres and tech investments. Yet at the same time, they are asked to absorb water stress, pollution, rising land prices, and ecosystem disruption. The question raised wasn’t whether development is needed – but what kind of development, under whose terms, and at whose environmental expense.

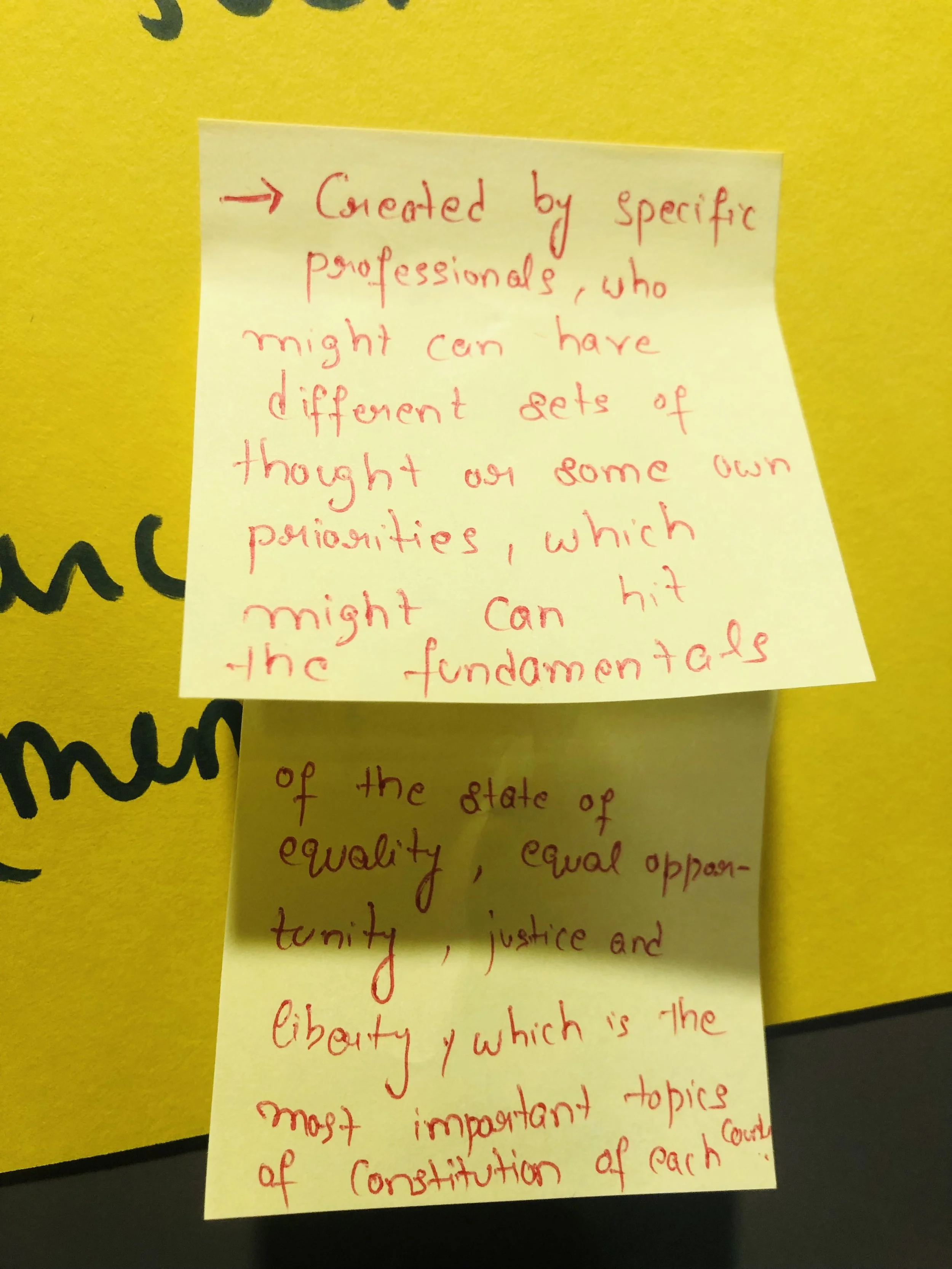

Another participant asked a deceptively simple but powerful question: who is actually funding this AI supply chain, and what are their interests? This opened up discussion around large tech corporations, venture capital, state industrial policies, and international investment flows – and how their priorities shape where infrastructure is built, whose knowledge counts, and which harms are deemed acceptable or “external.”

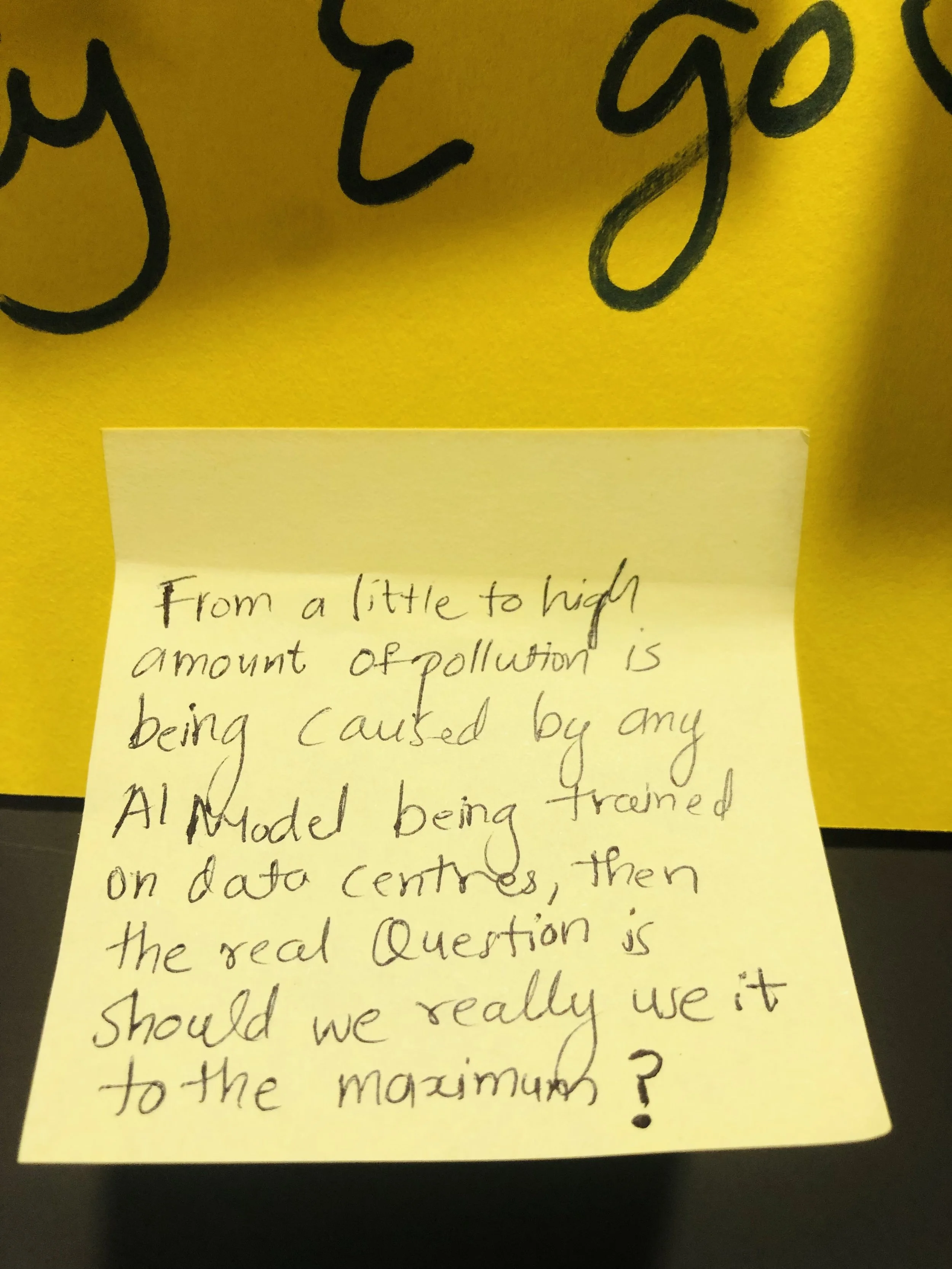

A further point that resonated across the room was the critique of how “efficiency” is often framed in AI discourse. One participant observed that efficiency rarely means “using less” – it often means being able to scale faster and consume more resources. More efficient chips lead to more deployment, more data, more extraction, and more energy demand, rather than less. This challenged the assumption that technical efficiency naturally leads to ecological efficiency.

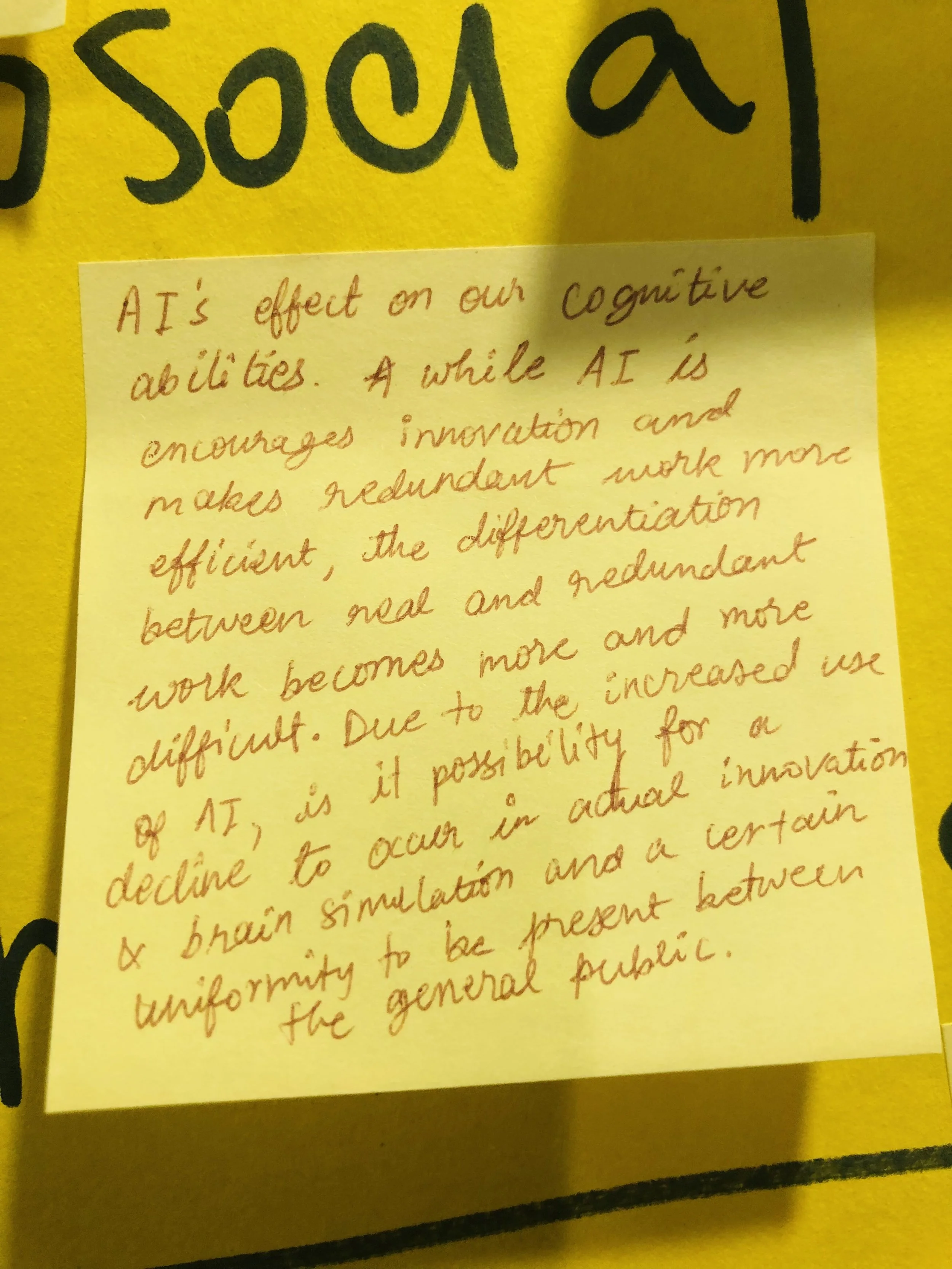

The discussion also moved beyond infrastructure into more subtle domains. One participant raised concerns about how AI systems might be affecting human cognitive abilities and habits – how over-reliance on automation could reshape attention, decision-making, memory, and learning processes. While this is harder to quantify, it opened an important conversation about AI not just as a technical system, but as something that is already reshaping how we think, relate, and perceive ourselves.

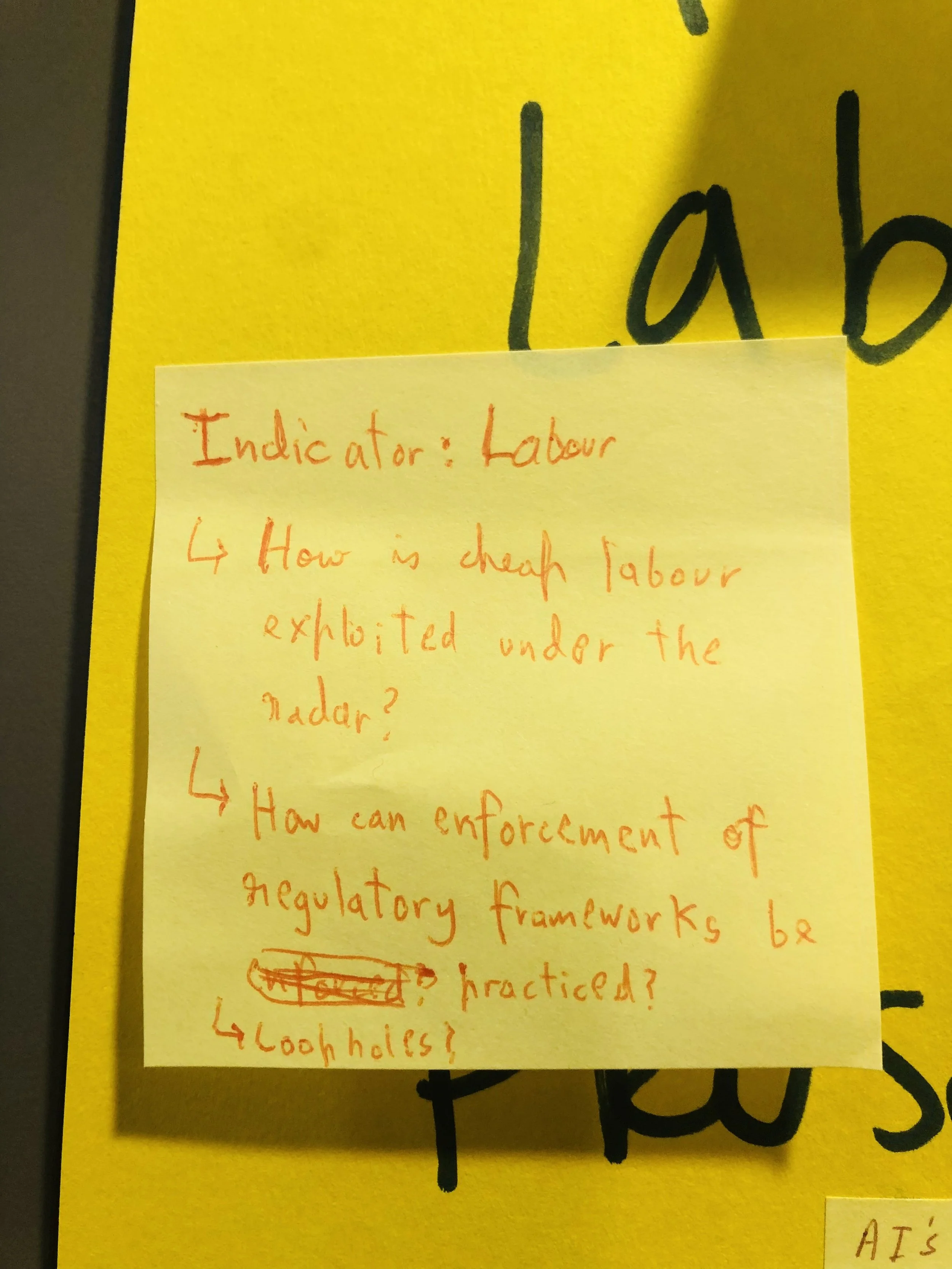

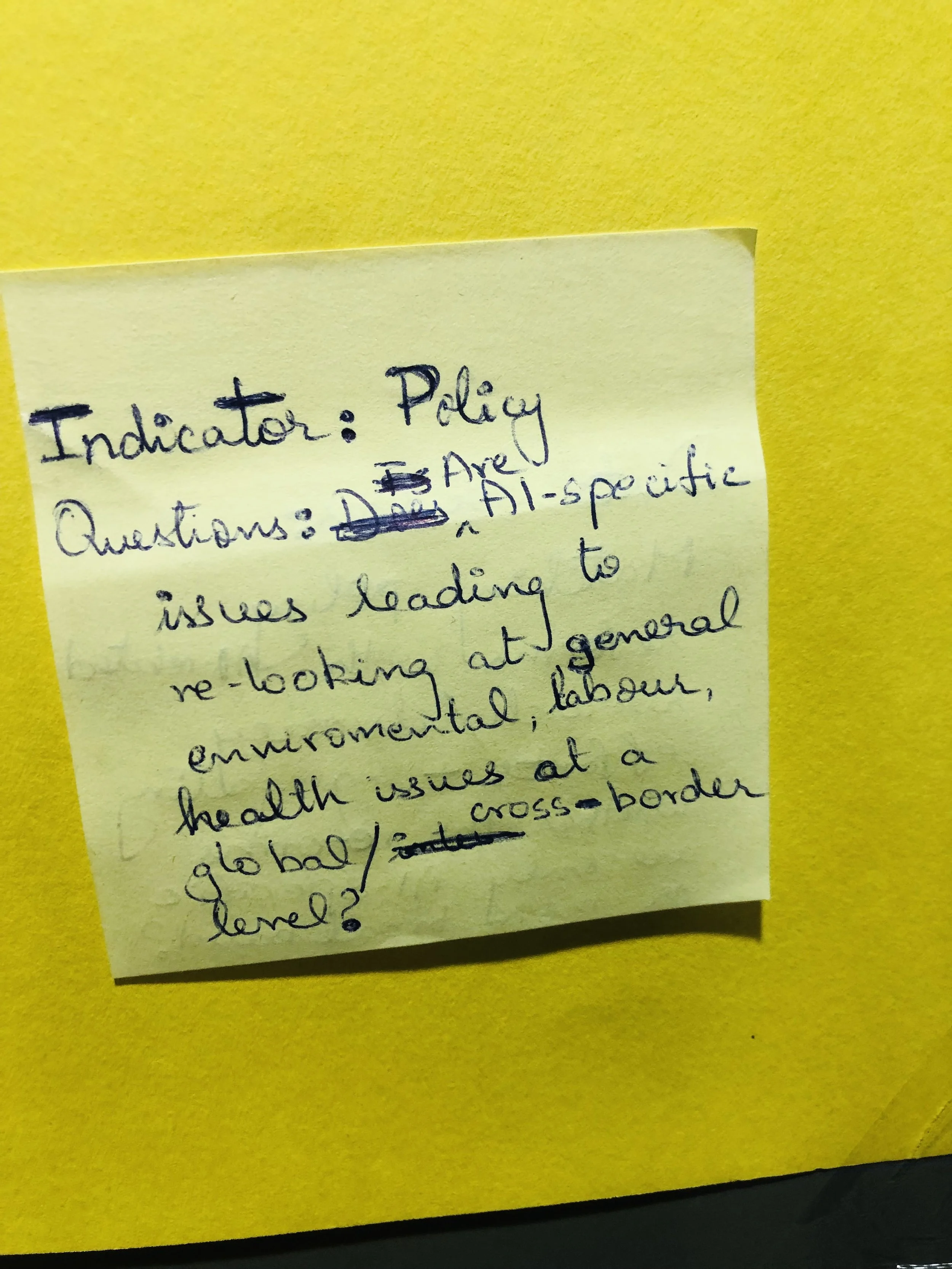

Finally, a critical governance question emerged: do we really lack regulatory frameworks – or are we simply not using the ones we already have? Participants pointed out that environmental law, labour law, data protection law, and human rights frameworks already provide significant tools to regulate many aspects of this supply chain. The issue, they argued, is not the absence of rules, but the lack of enforcement, political will, and adaptation to digital and AI infrastructures.

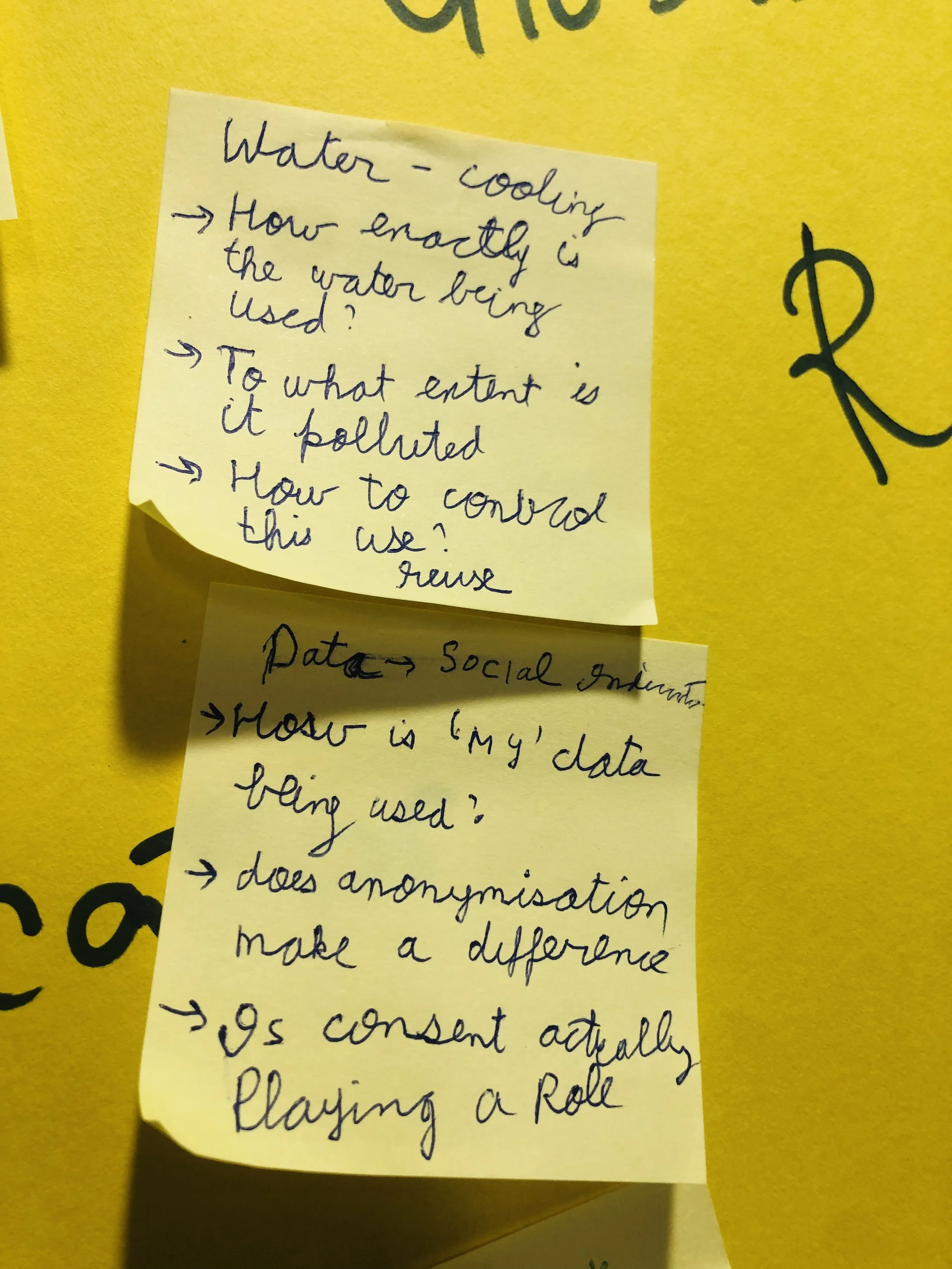

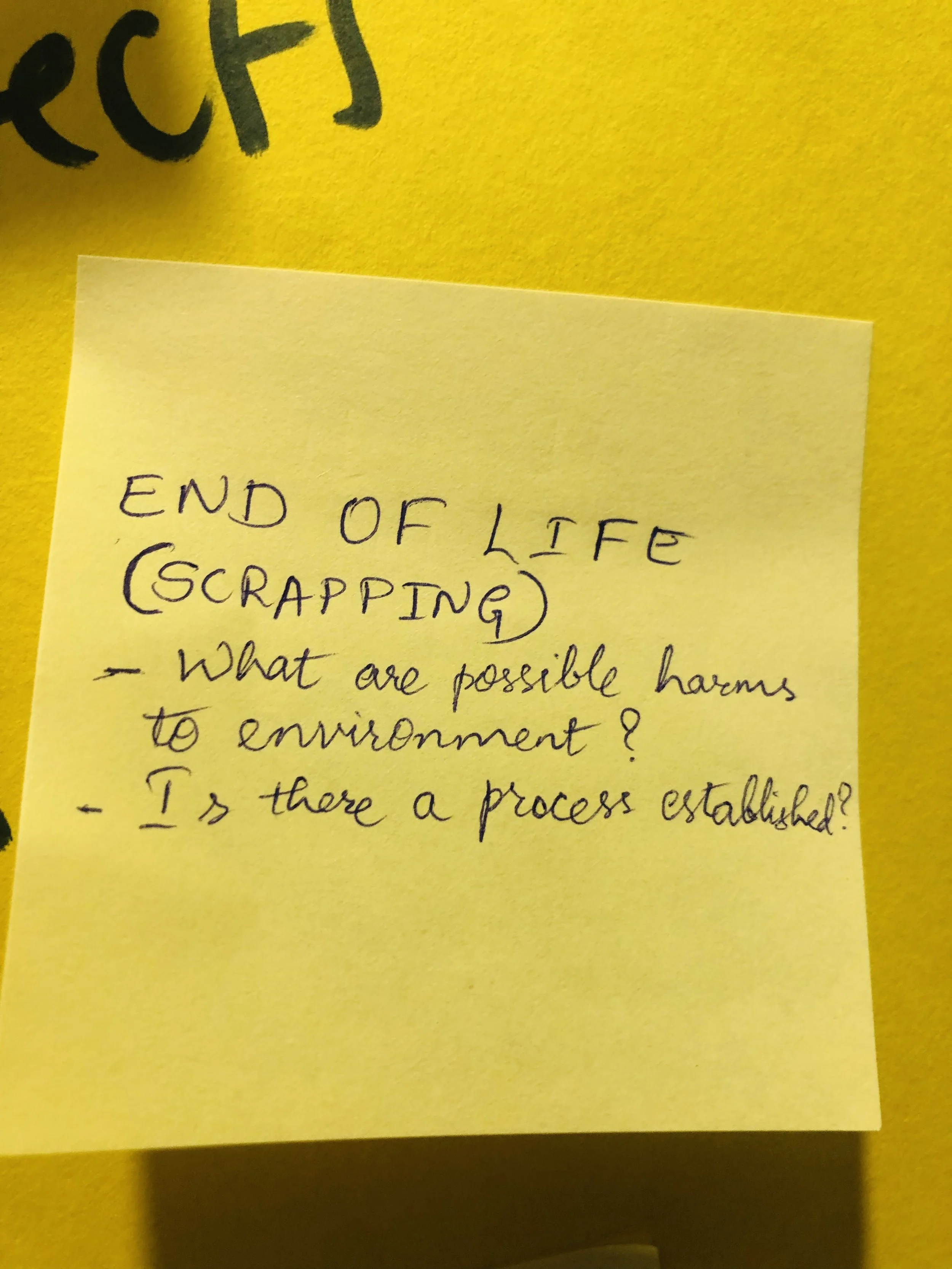

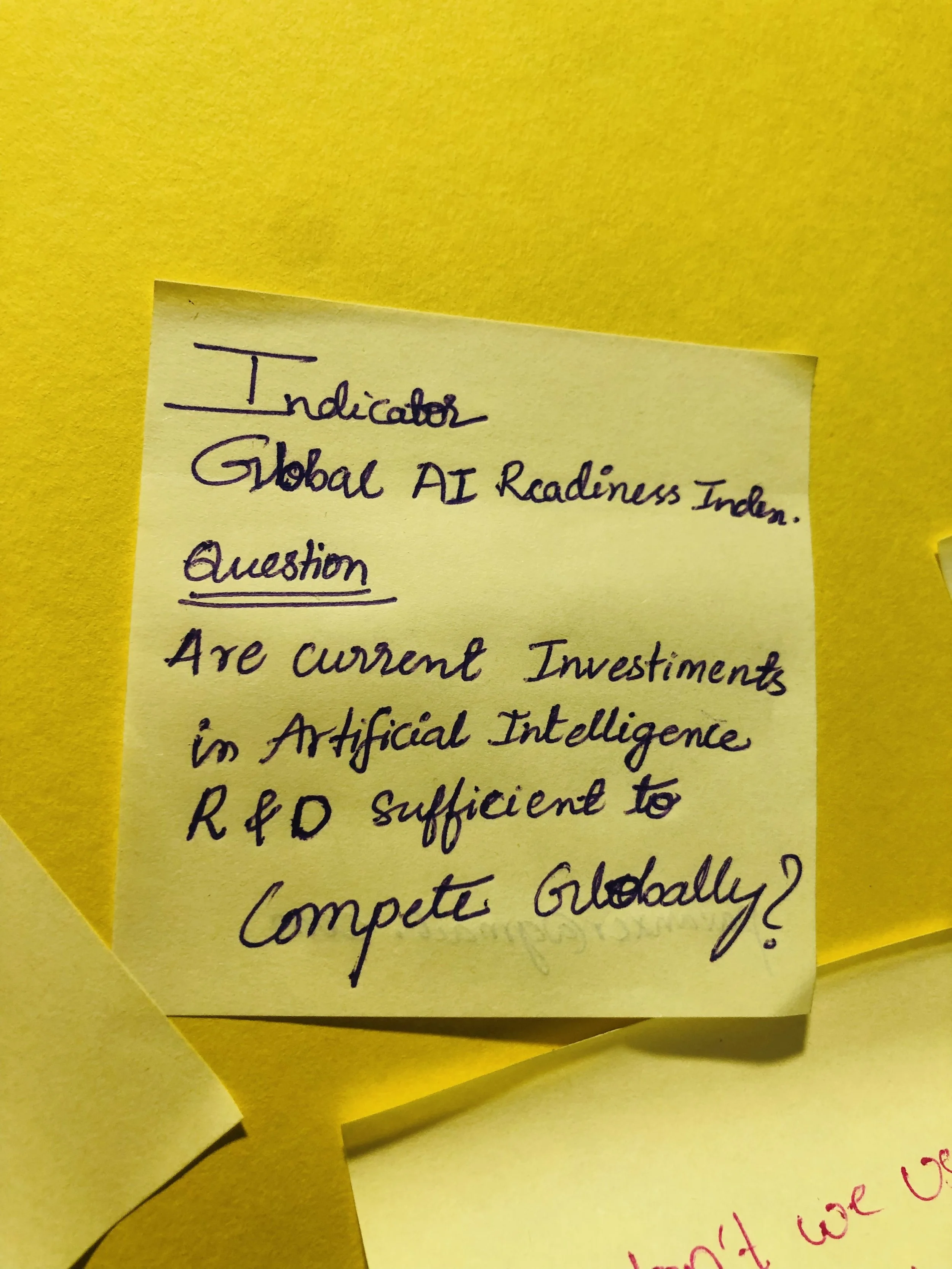

Toward the end of the session, we moved from diagnosis to collective construction. Using AIPJ’s AI Supply Chain Impact Framework, participants developed indicators and questions for assessing the impacts of model training, ranging from local water use and energy sourcing to labour conditions in data work. Just as importantly, they reflected on who should have access to this information, and how communities themselves could use it to strengthen their negotiating power around digital infrastructure projects.

By the end of the workshop, we hope AI no longer felt like something distant or abstract. It appeared instead as a dense web of material flows, power relations, ecological limits, and human decisions – something that is already reshaping landscapes and societies, and that urgently needs more democratic, community-grounded forms of governance.

Day 2: From Global Supply Chains to Community Rights

On the second day, Sara Marcucci joined a panel on the physical foundations of AI infrastructure, together with Siddhartha Malempati (Commons Collective), Maitri Singh (Digital Empowerment Foundation), moderated by Mili Dangwal (Digital Empowerment Foundation).

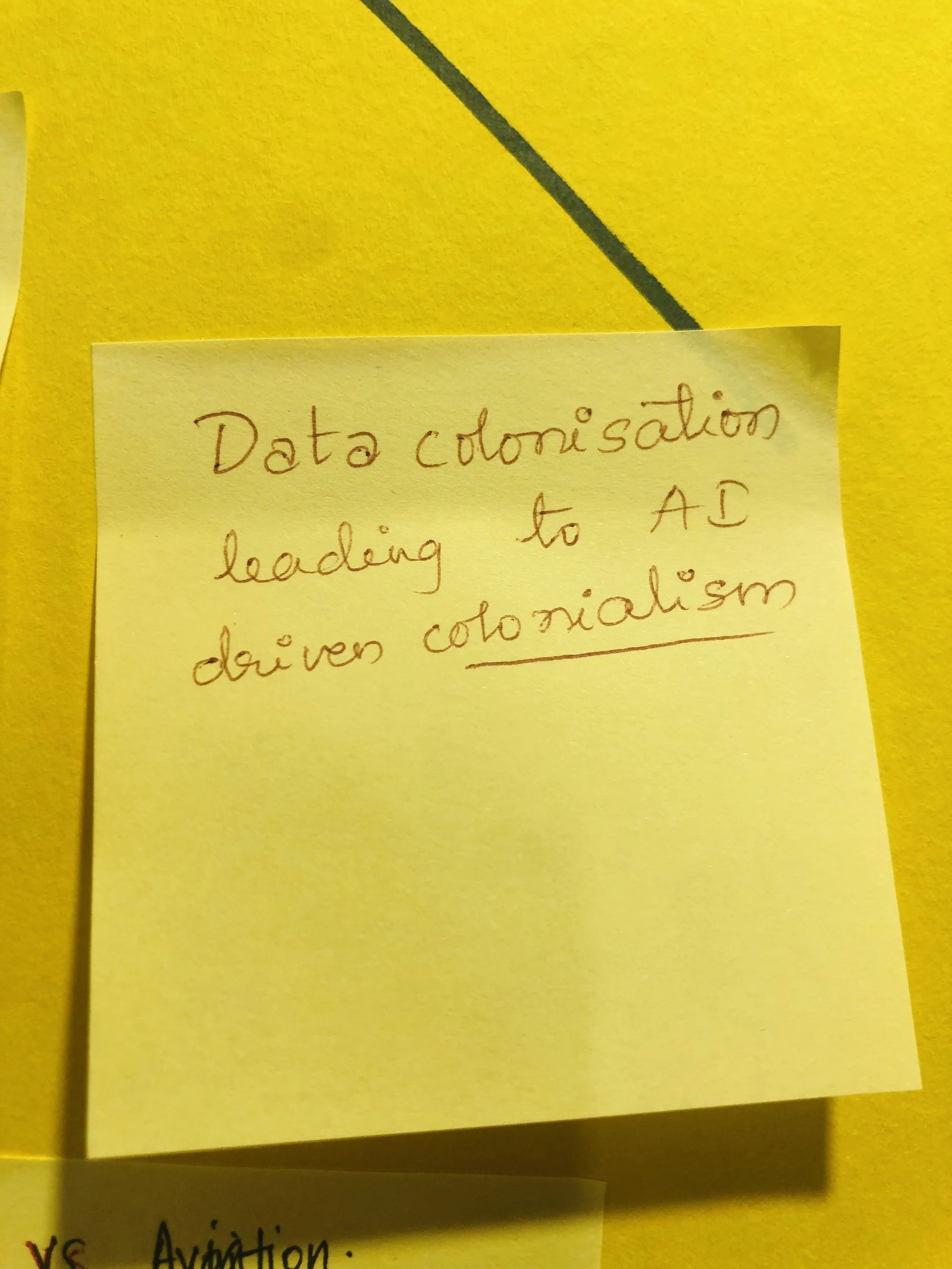

Sara’s intervention gave a global geography of AI extraction and inequality. She emphasised that large-scale AI infrastructure is not a neutral or localised investment, but part of a transnational supply chain that connects distant places through flows of minerals, energy, water, data, and waste.

To make this visible, she traced how contemporary AI systems rely on materials and infrastructures that link:

Mineral extraction zones, such as cobalt mining regions in the Democratic Republic of Congo or lithium brine fields in Chile and Argentina, where mining has been associated with land dispossession, toxic pollution, and the depletion of local water sources. These impacts are not only social but also ecological, affecting soil health, groundwater, and surrounding biodiversity.

Refining and processing hubs, like those around Baotou in Inner Mongolia, where rare earth refining has produced large toxic tailings lakes and long-term chemical contamination, with direct consequences for local ecosystems and human health.

Semiconductor manufacturing regions, including parts of East Asia–Taiwan, in particular–, where chip fabrication plants require extremely pure water and involve toxic chemicals (including PFAS “forever chemicals”) that pose risks to both worker health and surrounding environments.

Data centre corridors, such as those emerging in Hyderabad, Northern Virginia, Georgia, and parts of Southeast Asia, where large campuses demand vast amounts of energy, water, and land, reshape local infrastructure priorities, and put pressure on already strained resources.

And finally, e-waste destinations or informal recycling clusters in South and Southeast Asia, where discarded servers and electronics are dismantled under hazardous conditions, releasing heavy metals and pollutants into soil, air, and waterways.

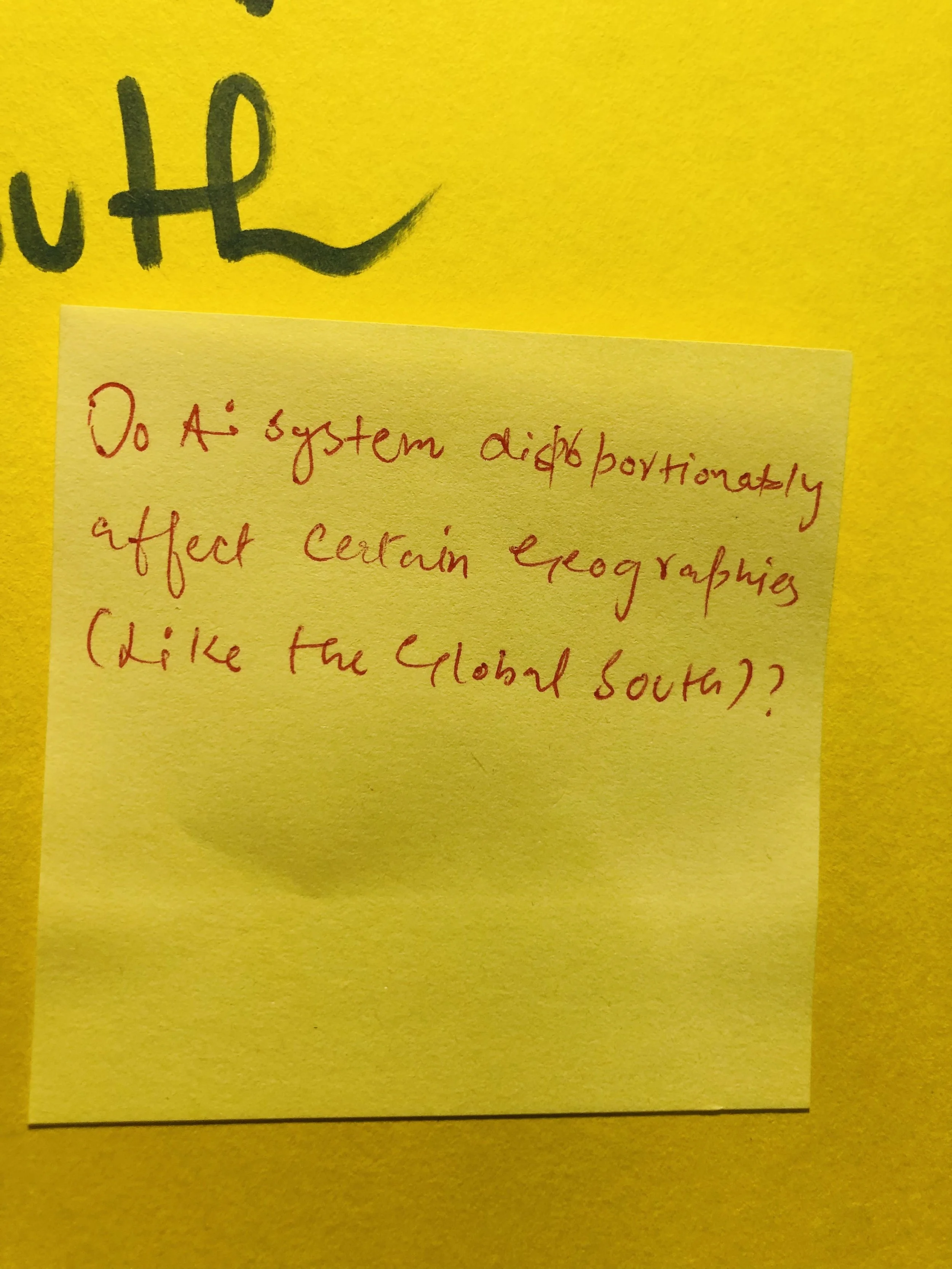

At each of these stages, Sara stressed, specific communities – often those with the least political and economic power – are made to absorb the social and environmental costs of a system whose primary benefits are concentrated elsewhere. These are not accidental side effects but structural features of how the current AI economy is organised.

Alongside Sara’s intervention, the panel benefited from two more perspectives that helped root these abstract supply chain dynamics firmly in local realities.

Siddhartha Malempati (Commons Collective) focused on the growing pressures that AI-driven data centres place on electricity systems and land markets. He unpacked how large data centre campuses demand enormous and continuous power loads, often equivalent to small towns or industrial clusters, and what this means for already stretched electricity grids.

He highlighted how, in many cases, public power infrastructure ends up being upgraded or redirected to support large private facilities, raising questions about who effectively subsidises these investments. At the same time, he pointed to the mismatch between local expectations and actual job creation: while data centres are often presented as engines of development and employment, they tend to generate relatively few long-term jobs once operational, while still driving up land prices and reshaping local economies.

Siddhartha also explored how the arrival of large tech campuses can distort local land markets – pushing land prices beyond what local residents, small farmers, or small businesses can afford, and contributing to displacement or loss of livelihoods. His contribution brought attention to how AI infrastructure is not only an environmental issue, but also a political economy and spatial justice issue, deeply tied to questions of who gets to remain, who gets priced out, and whose futures are being redesigned.

Maitri Singh centred her intervention on water scarcity and resource strain, drawing from concrete examples of Indian cities already facing chronic water stress. She explained how large-scale AI data centres require millions of litres of water for cooling systems, often drawing from the same aquifers, reservoirs, or municipal supplies that serve surrounding communities.

In regions where water access is already uneven and contested, this creates direct tensions: between tech infrastructure and agriculture, between industrial users and residential communities, between present needs and future sustainability. Maitri emphasised that these are not abstract trade-offs but very real, lived conflicts, especially for low-income settlements and peri-urban communities that already experience irregular access to water.

She also pushed the conversation toward potential responses: the need for stricter water accounting, transparent reporting by data centre operators, community participation in water allocation decisions, and policies that treat water not as an infinitely scalable input for digital growth, but as a finite, shared, and essential resource.

In the second round of the discussion, together with the audience, we reflected on the wider purpose of all of this: what is this for? What kind of technological, social, and environmental trajectory are we currently building?

Not in terms of innovation for its own sake, but in terms of the systems and dependencies being locked in – increasingly centralized compute, rising energy and water demands, large-scale infrastructure projects that shape land use and urban planning for decades to come.

This naturally led to a second question: who benefits from this trajectory, and who carries its burdens?

Much of the economic value and strategic advantage of large-scale AI systems is concentrated among a relatively small group of actors – large technology companies, investors, and state agencies pursuing technological competitiveness. At the same time, many of the social and environmental costs are borne by communities with limited power in decision-making: communities near data centers facing water and land pressures, communities near mining or refining sites dealing with pollution and health risks, and workers performing invisible digital labour under precarious conditions.

Finally, the conversation turned toward the question of alternatives.

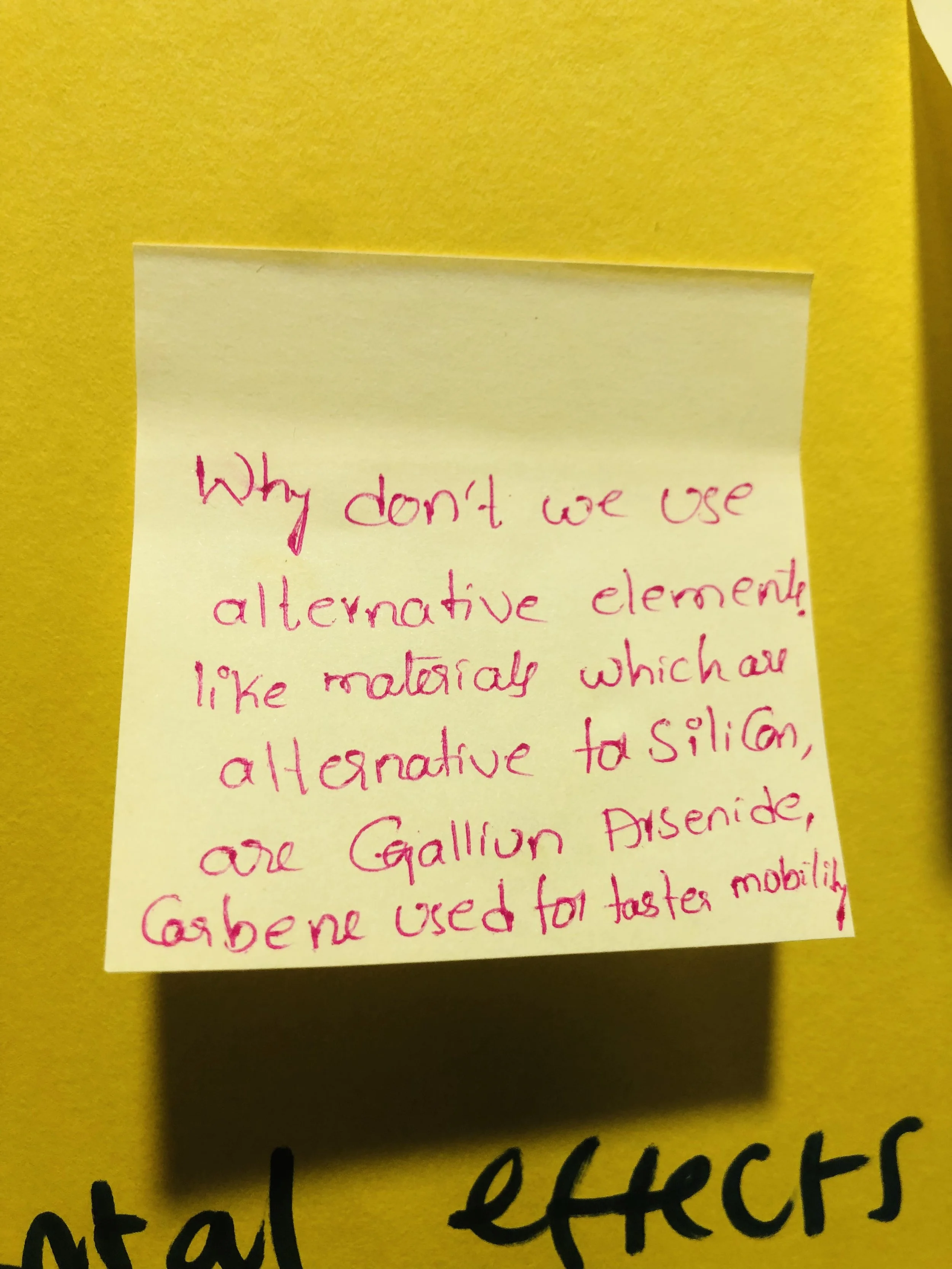

Rather than accepting this trajectory as inevitable, participants reflected on how AI development could be redirected toward models more aligned with ecological limits and social justice. This included thinking about:

Smaller-scale and context-specific AI systems rather than purely hyperscale ones.

Stronger community participation in infrastructure planning, not only consultation.

Governance mechanisms that treat affected communities as rights-holders rather than passive stakeholders.

Recognising water, energy, and land not as “inputs” but as finite and contested resources.

The discussion did not aim to offer definitive answers, but it instead attempted to made clear that these are not just technical choices – they are political and ethical ones. If AI is to be part of just and sustainable futures, the trajectory itself needs to become something we actively shape, rather than passively accept.